Hello Friends!

Welcome to Bright Green Futures, Episode Three: From Climate Fiction to Climate Action.

I created Bright Green Futures to lift up stories about a more sustainable and just world and to talk about the struggle to get there. Today we’re going to talk about the connection between fiction and action in the real world.

The Power of Story

The power of story in our lives is huge and multifaceted, and I can’t cover everything in a single post, but I want to give you a sense why the stories we tell matter, especially hopeful climate fiction, since that’s our focus on Bright Green Futures.

But let me start with a real-life story…

In 2004, twenty years ago, I was a young mother of three navigating the public school system. I’m a fan of public education, but despite moving to a suburb with award-winning schools, I found the system wasn’t getting kids the education they needed and the school board was a hot mess that refused to listen to the parents in their district. There were plenty of good people in the school system, but the school board had gotten used to no one attending their meetings and no one knowing what they were doing.

So I started to attend. And I wrote down what they said. And then I published it. It was just a newsletter that went out to some parents, but demand quickly grew. Not everyone in the district was on my email list, but my Spotlight on the Board notes got shared far and wide.

The school board was mad. Big Mad. They tried to tell me I had to stop writing down what they were saying in an open public meeting. And that’s all I was doing: transcription. I said if they didn’t like what I wrote, they could televise the school board meetings. Let folks decide for themselves.

This made them even more mad. They waited to see if I would go away. I did not. It took a year, but they eventually started broadcasting the school board meetings. Just on the local channels and it wasn’t recorded, so I kept taking my notes for those who missed it. By the time the school board had decided to put out their own detailed accounting of the board meetings, I’d already decided to run for office.

I served for four years, stepping down only because I had decided to pursue writing as a full-time career.

Now, I tell that story because I certainly didn’t start out planning to run for school board. I didn’t even have a specific agenda of what needed to change—I just knew that operating in secrecy had gotten us where we were and there was no disinfectant like sunshine.

All I really did was show up, every month, month after month, and write things down.

It’s surprising how powerful just showing up can be. And writing stuff down. And sharing it. What shouldn’t be surprising is that one action can lead to another. Once you decide to do something, the next steps often reveal themselves. We sometimes think we have to have everything mapped out, and planning is great, but as the saying goes, great plans don’t often survive their encounter with reality.

How does all this relate to climate fiction?

At a fundamental level, narrative drives everything we do—what we believe is right and wrong, how we think the world works, what we believe we should strive for, what we value, what we think is possible. I have a strong core belief in the public’s right to know, especially with something as important as public education, and that narrative plus a serious lack of respect for authority meant I had the audacity to show up and write stuff down.

“Narrative” is just a term for the stories we carry around in our heads that tell us how the world works. “Beliefs” and “values” also help us decide what we can, and can’t or at least shouldn’t, do with our time on the planet. Rules of Living is practically an entire self-help genre, and religions and philosophies build whole narrative frameworks to help folks decide how to live.

In a real sense, our crisis-filled time—sometimes called the polycrisis and that includes the climate crisis—is an indicator that the old stories we’ve been using are no longer fit-for-purpose. My friend P.J. Manney calls this the old mythos, and her thesis is that we’re in desperate need of a New Mythos for this new era. We need new stories to lead the way, and that goes double for the climate crisis.

I follow Solitaire Townsend, futurist and climate solutions entrepreneur, on social media and she had this wonderful post on Mastodon:

I think Solitaire and P.J. are both right. But there are a lot of aspects to the why and how of stories motivating people to action, and I want to dive in a little bit, even if we can’t fully explore everything in one post. I’m sure I’ll be returning to this topic in the future.

I think there are two fundamental mechanisms by which stories change what actions we take:

We are influenced by what we see people doing.

We are influenced by new ideas that unlock our imaginations.

Who We See

First, we are a social species, and peer pressure isn’t just for teens—it’s built into the entire fabric of our society. We’ll outlaw certain behaviors but a whole raft of other behaviors are socially influenced, for good and for bad. If your friends smoke, you’re more likely to. If you see your neighbors putting in solar, you’re far more likely to install your own. It’s not that we’re mindless drones, but we are a social species, and looking to those around us for all kinds of things—support, signs of danger, what’s “normal” and what’s not—is deeply encoded in the folds of our brains, back in the parts that understand we need other people to survive.

But we’re not just influenced by friends, family, and neighbors. We have para-social relationships with celebrities. We joke around with the post office worker. And we have literary relationships with people who aren’t even real—characters that an author created on the page or an actor breathed life into on the stage. I recently went to see Fat Ham, a queer Black retelling of Hamlet, BBQ and Shakespeare on the stage together. It was glorious. Go see it, if you have the chance. Each of those characters and their choices were so alive, so vibrant, they’re still haunting my brain weeks later.

Anyone who reads or watches movies or TV doesn’t doubt the impact stories and their characters can have.

New Ideas

So we’re influenced by people—even fictional ones—but we’re also influenced by ideas. And this is where hopeful climate fiction can really shine. When an author conjures up a fictional future reality with new ideas about how we relate to one another, how we live and consume everything from energy to food, those ideas flit around in our brains, combining with other ideas and generating even more. Stories are the perfect delivery mechanism for this, slipping right past all our built-in biases, casting aside dry reports and graphs and policy documents, and delivering delicious new ideas straight to the part of our brains that lights up when we encounter novelty. And once inside, those ideas cook and simmer and suddenly actions that seemed impossible in the real world, suddenly are a little more reasonable.

Maybe I can’t set up a mall commune to live in, like the character in my just-released story, Tower Girls, but I can join the local Buy Nothing group or sign up to help in the community garden.

This short snippet shows that kind of realization in the character:

“I heard you’ve formed a collective,” Zita said. “Women of the Tower is a seriously kickass name.”

Aeris smiled. “I didn’t even know that was a thing you could do.”

Fiction can educate us about the things we didn’t even know we could do without all the PowerPoint slides and Zoom meetings. I’ve learned something climate-related from almost every climate fiction story I’ve read. And I certainly have some of that educational aspect in nearly every one of the stories I write. And it’s usually not the facts and figures of science but how the technology influences and shapes our lives and choices.

Here’s a short excerpt from my newly-released short story, Slimy Things Did Crawl, where a trawler crawls along the bottom of the sea, carefully cleaning microplastics off the ancient mineral-rich nodules… and the crew of three agitate each other.

“You don’t have to be so mean to him,” I hush-whisper.

“He gets on my nerves.” She gestures me over to Anders’ station, and he did leave in a huff, so I hustle over to ensure everything’s running smoothly. While Ianira monitors marine life, Anders is in charge of the actual reclamation. The AI uses low-light vision software to make sure we don’t accidentally squish anything that slips past Ianira’s notice. Then two dozen robotic arms pick up the nodules, use a meticulous washing technique to remove most of the microplastics, take small samples of the epifauna and cores of the nodules themselves, then delicately set them back in place. Non-invasive mapping of the entire system at the speed of a very slow sea slug.

We’re in the dead zone precisely to perfect our microplastics cleaning of the nodules with less risk to sensitive ecosystems. With the worldwide ban on new plastic production set to kick in next year, harvesting the plastic we’ve strewn haphazardly around the planet could become economically viable. And mining companies still have their eyes on the nodules, with all their rich, rare-earth metal content. Never mind these rocks are millions of years old and impossible to replace. The mining folks also do their best to ignore the Clarion Clipperton Zone disaster. The bastards strip-mined a ton of nodule beds in the North Pacific and caused a cascade collapse of fisheries as far away as Seattle. Sediment plumes could be seen from space. The habitat wreckage was incalculable.

One doesn’t bring this up with Ianira, unless one wants a Battle Royale, you against her and all her danger fish.

Anders is smart enough not to go there, but his whole presence, the entire purpose of our endless trawling of the ocean floor, is a reminder of it. Our mission is funded by the World Science Organization, but the trawler and the floating research station above are based on mining tech, part of the ongoing attempt to rehabilitate the industry’s oily reputation. But everyone knows they have an eye on the nodules, and Anders’ experience in the industry gives him the skills to do his work… and the stench of mining will never come off him, as far as Ianira is concerned. If the dead zone is sufficiently dead—if Ianira’s biological surveys show the marine life here is utterly mundane—then the next trawler will scoop up nodules by the bucketload rather than delicately cleaning them and returning them to the ocean floor. But if Ianira can prove this is a unique ecosystem, we might get the whole zone declared a Marine Protected Area.

Half of why I stick around is to keep the two of them from coming to blows.

This deep-sea trawler is just the setting of the story, but it is also core to the interpersonal stakes between the characters. And it’s a tiny tutorial on the importance of not destroying the world’s marine ecosystems with deep-sea mining, which is a very important and pressing issue here in 2024. One reader of the story has already come back to me and said, “Sue! That deep-sea mining stuff was in the news! Did you see it?” Yes, I did. And I hope every person who reads the story has that same awareness lift, that alerts them to this issue.

Being influenced by fictional people and new ideas are just two ways stories can influence us.

Other aspects include things like the well-known increase in compassion with reading, the fact that people who don’t read science fiction may find climate fiction intriguing and relevant, and that those who don’t want to think about climate at all might re-engage if they read a climate story that’s inside a hopeful framework.

And those are just the impacts on readers.

Climate fiction writers often strive to live a lifestyle that accords with what they’re writing. Writing these stories is an extended thought experiment about how we get out of this mess and the more people who are doing it, the better. Which is why students should write cli-fi, scientists should write cli-fi, anyone called to write it should give it a go. It’s an exercise in How To Survive the Anthropocene. Given the leadership at high government levels is, and has been, lacking in serious ways, given the many malevolent forces working to keep the status quo going as long as possible, no matter the damage, it’s really up to all of us, both individually and collectively, to not wait around for someone else to fix this.

We need a million stories about a million people taking action. The good news is that is starting to happen, both the stories and the people taking action in the real world. None of us can do this alone. And that’s not the right approach anyway. We need to act collectively—and tell stories about how to do that—and one of the most basic parts of that is not electing reactionary governments. If you put someone into office who’s bent on environmental destruction, there will be backsliding. Those in power can do incalculable damage. And that has to be fought. But no matter who is in charge of the country, they can’t stop you from showing up at your local city council and demanding they install solar. They can’t stop you from attending your local school board meeting and taking notes. People in power seem all-powerful, but the real power remains in simply showing up, caring, and taking action. We are far too numerous for them to stop us.

Action Feeds Action

Action feeds action. Ideas feed ideas. All of it combats anxiety about the climate crisis, which can debilitate us and cause us to look away.

Stories give us inspiration, make us feel less alone, help us navigate the terrifying reality of the climate crisis, show injustice, give us a brief gasp of joy, and help us understand what some of the issues are in a concrete way.

The battle is no longer to convince people that climate change exists or even that we’re to blame for it. The vast majority of people now understand those facts. The battle is to move people from inaction to action. To defeat the narrative that we’re helpless, hopeless, and doomed. If we can do that, I can’t begin to imagine all the ways people will work for change.

But I will give it a try in my stories.

And that piece—how we can use fiction to connect individual actions to the overall fight—is something I’ll have to cover in a later post.

For now, I’ll leave you with this quote from the Good Energy project about the power of story:

Bright Green Futures is a weekly newsletter/podcast. Check out the Featured Stories and Hopeful Climate Fiction lists for further reading. The best way to support the show is to subscribe and share the stories with your friends.

LINKS Ep. 3: Climate Fiction to Climate Action

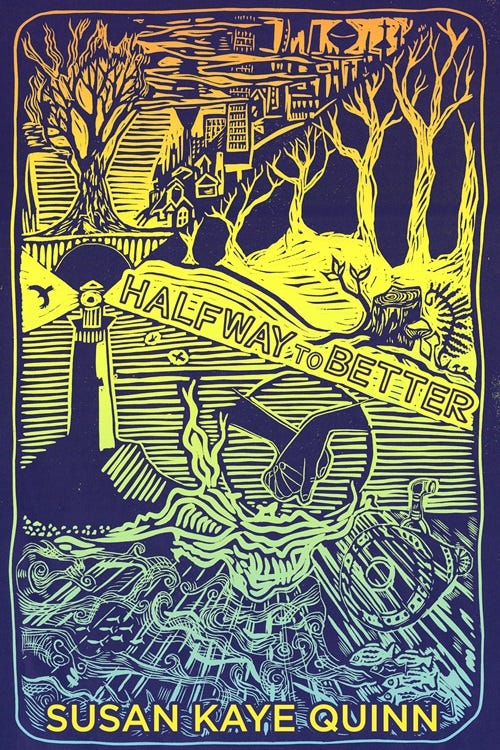

The two stories I discussed in this pod are part of a collection called Halfway to Better, which is available for preorder and releases on Earth Day, April 22nd. The individual stories are free to read—I hope you’ll download them and give them a try.

Halfway to Better (releases April 22nd) by Susan Kaye Quinn

Share this post