Hello Friends!

Welcome to Bright Green Futures, Episode Five: Structure in Climate Storytelling.

I created Bright Green Futures to lift up stories about a more sustainable and just world and to talk about the struggle to get there. Today we’re going to talk about the connection between the structure of stories and how we think about the climate.

A few months ago, I had an aha moment about climate storytelling, one of those intellectual jolts that seem to reorient the stars for a moment. I had belatedly discovered Amitav Ghosh’s 2016 non-fiction book, The Great Derangement, in which he confronts the literary community about their unwillingness to write (or at least publish) climate fiction, relegating it to the apocalyptic tales of science fiction, a genre which capital-L literature apparently regarded as a lesser form.

Now I’ve been writing climate fiction explicitly since 2020 (implicitly since 2011, if you count my pharmaceuticals-in-the-water-made-us-mutants Mindjacker story), and all along, I’ve been struggling with the type of climate fiction that Sci-Fi produced as well, but it didn’t even occur to me that the literary fiction folks were having the same issue, namely an unwillingness to write seriously about the climate, beyond apocalyptic thrillers, much less publish hopeful near-future climate fiction.

Some of that has changed—Kim Stanley Robinson’s Ministry for the Future, published in 2019 is the famous example—but Stan’s book is also the exception that proves the rule.

In The Great Derangement, Ghosh’s arguments are nuanced and deep, and the book is a must-read, particularly how he connects imperialism to not only climate-change but the structure of the novel itself, and how Literature has difficulty engaging in the topic of climate for the same reasons that society at large does.

But this particular sentence from the book truly arrested me:

At exactly the time when it has become clear that global warming is in every sense a collective predicament, humanity finds itself in the thrall of a dominant culture in which the idea of the collective has been exiled from politics, economics, and literature alike.

This is the rejection of the hero’s journey! It’s the clarion call for a New Mythos! It is the need for a change in the “dominant culture” that everything from hopepunk to solarpunk to the climate movement itself have been attempting to articulate. This change was also deeply woven into the climate novels I started to write in 2020, but I was toiling in my own silo without realizing I was part of a larger zeitgeist that was already swelling.

I had the great fortune, just a few weeks ago, to meet Mr. Ghosh during his visit to the City of Asylum in Pittsburgh. He was just as articulate as you’d expect and even more delightful. He said there had indeed been an upswelling of climate fiction since about 2018, but that he felt it mostly still suffered from apocalyptic storytelling, and interestingly, he thought the developed world tended to see the climate crisis as a problem of fossil fuels whereas the global south saw it more as a problem of over-consumption by rich nations and the still-present geopolitical impact of colonialism. When I asked him what kinds of climate fiction he would like to see in the world, he said he would like to see more stories connected to the history of their place on the planet. In essence: think local, but also know the history of that place and its peoples. Which is very much the lens through which Ghosh writes his own fiction.

I personally think it is both—fossil fuels and their transnational companies are a destructive force and decarbonization is dead-central in the climate fight, but also the geopolitics of why it’s so difficult to change to that decarbonized world are bound up in the history of colonization and imperialism, something that’s not so much history, more of an explainer for how things operate in the present-day. All of which means the world’s people are held hostage by ideas that serve those in power but ultimately are mal-adaptive and self-destructive for the rest of us. Ghosh articulates well the source of the problem: the idea of the collective has been exiled (and intentionally so by the narratives developed to justify imperialism).

I see many of these movements, in both in literature and in activism, as a reclaiming of that idea, a re-embodiment of the collective in our stories. And not in a singular way, but in a multitude of ways, just as humanity isn’t one collective but a thousand different networks, interlacing, overlapping, stronger for those bonds and weakened when we’re isolated.

How That Works in Climate Fiction

Back in 2020, as I was writing my climate fiction novel series, I was working through how to represent that collective in a storytelling form that wasn’t really built for it. We’re supposed to have a single hero. They set out on their journey, overcome obstacles, conquer the enemy, and return triumphant. It’s easy to see how that maps to a story of imperialism. Which is why I was beyond excited when I discovered Gail Carriger’s Heroine’s Journey, which articulates a different kind of story structure. (As an aside, the two journeys are not gendered, but patriarchy has long said that it’s men’s stories that matter most, and those have been framed as Hero’s Journeys. The nomenclature is a holdover.)

In Gail Carriger’s Heroine’s Journey, the Heroine isn’t called to adventure. Her initial call-to-action is a break in her family bonds. She suffers and experiences loss when something happens in the world that is destructive to her connection to family and community. She then sets about her journey trying to literally rebuild society. It’s not a self-focused journey of discovery but an outward-focused story of gathering allies, making bargains, and negotiating the networks that she’ll need to restore and rebuild. The hero is strongest when everything is stripped away and he has to discover his deepest innermost power. The heroine is strongest when surrounded by her friends. The hero is bent on destruction of the enemy. The heroine is open to compromise and interested in restorative justice not revenge.

These are broad storytelling archetypes, and both journeys are legitimate expressions of human experience, but that’s exactly the point: only one of these has, historically, be considered the “proper” framework for telling a story. The heroine’s journey was relegated to romance and buddy comedies. Which are some of the most popular genres, but I digress.

My point is that the framework is there, but it’s been denigrated and sidelined, and I was incredibly eager to sharpen my pencil and reclaim the Heroine’s Journey in everything I was writing. But I wanted to go beyond that template and really explore how to reclaim community and connection in storytelling.

If you look at the cover art for my Nothing is Promised series, you will see that the four novels, put together, make one larger image. The titles form a somewhat cryptic sentence. And if you read the stories, you’ll see each has a different protagonist, with the main mystery of the series passed off, baton-style, from one protagonist to the next… with the final book doubling down on that structure in a way I won’t describe, to avoid spoilers, but it was intended from the beginning. The idea was to use the structure of the series, in everything from artwork to titles to POV, to reinforce that sense of connection: that we each have a part to play in the larger story. We don’t have to be the hero in order for our part to matter. A lot.

Kim Stanley Robinson, at a climate storytelling conference I attended, talked about the many POVs he has in Ministry for the Future, and how, as a writer, you risk a certain disconnection with the reader when you don’t adhere to that modern storytelling trope of being deep inside your character’s head and taking the reader along for that Hero’s Journey that they expect. In a way, we’re battling against many decades of reader experience with stories that follow that template. But, Stan said, we have to try, anyway.

I think grappling with how to tell stories that reclaim the collective but don’t lose the reader—that dig in and find new and creative ways to entrance, entice, and otherwise entertain, as all good stories must—is the essential question climate storytelling will grapple with.

Which is why we need so many new stories. I can’t think up all the ways to get creative with this on my own. Neither can Stan. But with the energy of a thousand creative brains humming away, we can reinvent the future to be what we, as one of many interconnected species on the planet, really need it to be.

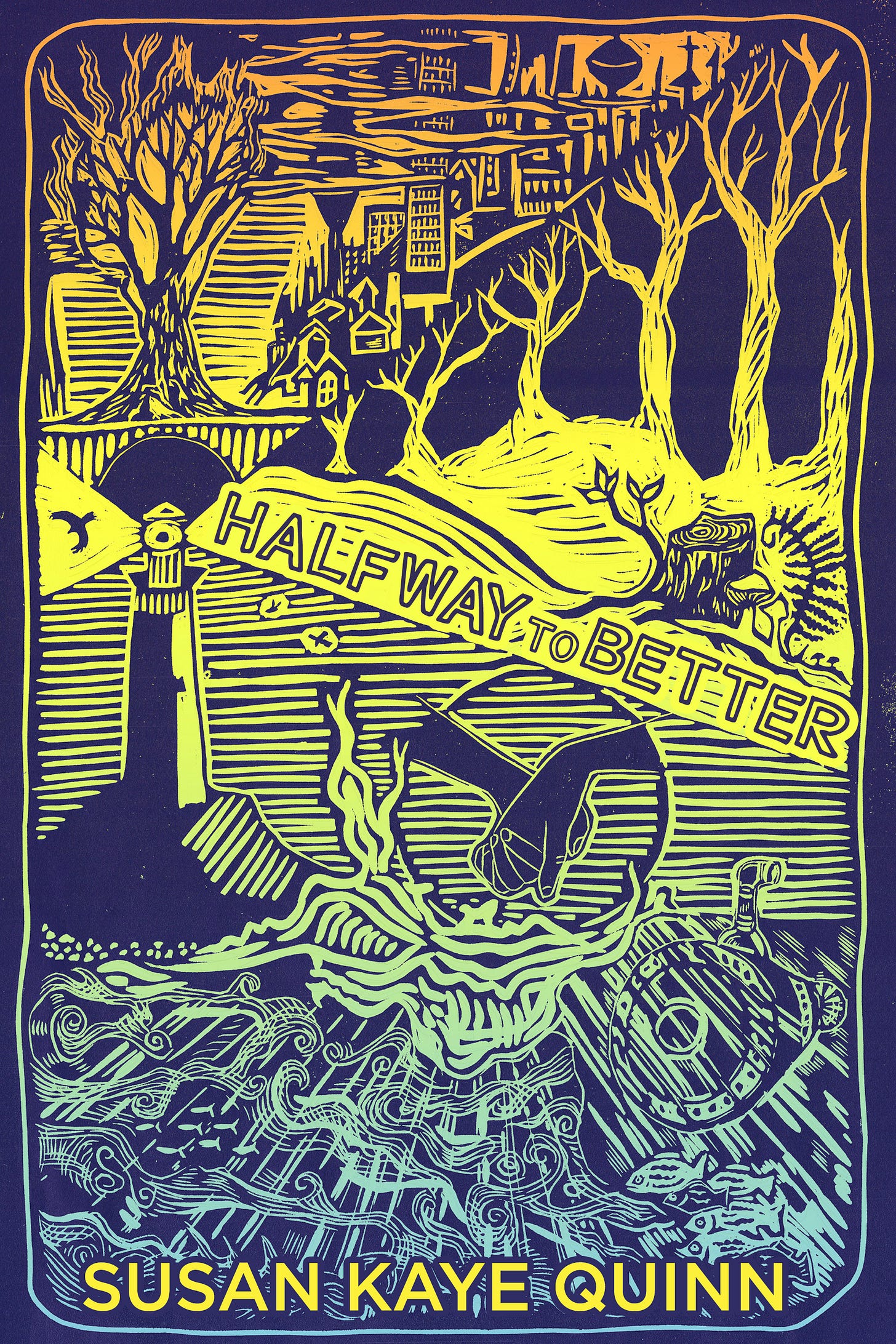

This episode of the pod is scheduled to post just before Earth Day, which is when my collection of short solarpunk stories, Halfway to Better, is set to release. These stories vary in their protagonists and settings and conflicts, but they’re all imagining us battling the climate crisis and finding each other.

I wanted to do something special with the artwork for that collection as well. Even though the stories are not explicitly in the same “world,” they are literally all potential futures for our world. So I contacted a local artist whose print-making work I loved, and we took this amazing creative journey together to craft a single image that contained the idea of the collection as a whole and yet gave each of the individual stories, which would be published separately to make them more accessible, a cover that was recognizably taken from the whole.

The result has astonishing beauty beyond even what I had hoped for. The artist sent me a framed print that is hanging in my office. I can’t really describe the joy it brings me, but I hope you will check out his work.

Here’s an excerpt from the last story in the series, I Came Home From Saving the Rainforest, where a young woman finds her grandfather has cut down her favorite tree.

My feelings are drowning me now, so I shout more than I should and run out into the rain and cry with the clouds.

I was born into a world on fire, and it’s only gotten hotter.

The trees are our lungs! How can we breathe when they’re gone?

How can you not see?

The world is changing.

Even the coal miners’ kids are installing solar now. They’ve turned shipping containers into homes for climate refugees and built solar cities that can survive hurricanes. We’ve learned how to make plastic from seaweed and grab free energy from the wind and the sun, yet the work has only begun. It will take my entire lifetime to undo the damage done during yours.

Why can’t you learn something from me?

We have so many real, human conflicts in the climate crisis. It’s so vast and overwhelming and terrifying… it’s the most spectacularly difficult thing we’ll ever do, figuring out how to survive this, how to live sustainably on the earth. And there will be a million stories born of it that we’ll need to tell to help navigate the way.

By definition, we’re not going to get there by doing things the way we’ve always done them before. Including the way we tell stories.

There’s so much more on this subject, including non-Western storytelling structures and experimental narrative styles that are perhaps more accepted in short fiction and literary fiction, but those topics are an entire post to themselves.

I’ll finish off with a final quote from Amitav Ghosh, and again, I highly encourage you read his book:

When future generations look back upon the Great Derangement they will certainly blame the leaders and politicians of this time for their failure to address the climate crisis. But they may well hold artists and writers to be equally culpable—for the imagining of possibilities is not, after all, the job of politicians and bureaucrats.

Imagine the possibilities. It’s not the tagline for this show for no reason. I’m trying, as a writer, to do exactly that, but I can’t do it alone. That’s why this pod/newsletter exists. To bring together the stories, the writers, the readers and listeners — it’s a collective act that I hope will be generative for story creators and story readers alike. We have always inspired one another, building upon the shoulders of giants to do better, reach farther, and imagine higher.

We can do this, friends.

Thank you for coming along on the journey.

Bright Green Futures is a weekly newsletter/podcast. Check out the Featured Stories and Hopeful Climate Fiction lists for further reading. The best way to support the show is to subscribe and share the stories with your friends.

LINKS Ep. 5: Structure in Climate Storytelling

The Great Derangement by Amitav Ghosh

Ministry for the Future, Kim Stanley Robinson

Heroine’s Journey by Gail Carriger

Nothing is Promised series by Susan Kaye Quinn

Share this post