Hello Friends!

Welcome to Bright Green Futures, Episode Seven: Climate Fiction in the Larger Climate Movement.

I created Bright Green Futures to lift up stories about a more sustainable and just world and talk about the struggle to get there.

In previous posts, we’ve talked about how climate fiction can motivate us to climate action, and how the structure of the stories themselves can be used to re-center the collective, not just the individual, situating characters (and readers) as part of a larger story. Today we’re going to dig into climate fiction’s place in the larger climate struggle and how understanding activism and movement building can help us to portray in fiction how change really works.

But first, I have to tell you about the Sustainability Salon.

Sustainability Salon

The Salon is exactly as it says on the tin: a gathering of passionate intellectuals, artists, and activists to talk about issues related to sustainability. As a word nerd, I appreciate the alliterative construction, combining a forward-thinking modern word—sustainability—with salon, an older multi-faceted word that evokes 19th Century French parlors, and which is now having a renaissance in describing any kind of intellectual discourse, but especially in person.

The words alone had already hooked me. The Salon itself fulfilled all that promise.

When I moved to Pittsburgh in 2021, I had zero local friends and I was going through some tough personal-life things, but I was determined to connect, put down roots, explore the city, and find my people… which was extraordinarily difficult to do with COVID still surging. I could tell Pittsburgh had a thriving arts community and a vibrantly diverse city life—more than I expected for a city so much smaller than the Chicago metropolis where I’d lived for twenty years—but getting connected to that community was difficult, especially when I was living on the outer periphery of the suburbs. I had farms and forests in my backyard, which I loved, but that didn’t necessarily bring me in contact with like-minded folks.

It was ironic but perhaps inevitable that I would only meet Maren Cooke, host of the Sustainability Salon, on Facebook. A mutual friend said, Oh, you’re in Pittsburgh now? You should meet my friend Maren. And they were so right.

Dr. Cooke is brilliant planetary scientist who has done post-doc work at MIT and for NASA, but now she’s a prolific environmental activist, the kind of person who creates spaces and connects people. She hosts the Sustainability Salon in her rewilded backyard, and she’s connected to everyone and involved in everything, not just climate issues but social-justice and equity.

She’s a magnet for my kind of people, so it’s not surprising I was drawn right in. The Salon itself attracts serious, policy-oriented, action-oriented, nerdy people (like myself), and in fact my first Salon was as a presenter. Nothing like jumping in feet first!

But that’s also my style… and it turns out I was very much not the exception. These were serious people who got things done—as activists in the local community and the broader political and justice-fight arenas—and here I was giving them a talk about hopeful climate fiction and the role it could play in the climate fight.

I thought they might laugh me out of the backyard, or more likely, sustain some polite applause before they got back to their important work and serious lives. Instead, they had brilliant, evocative questions and were absolutely ready to consider hopeful climate fiction as a possible tool in the larger movement toolkit. It was exciting, enliving, and deeply encouraging.

And that was just my first Salon.

Sustainability Salon: Movement Building

Soon after, a multi-Salon series on movement building guided by long-time activist Penn Garvin absolutely riveted me and shifted my thinking on several things. I’m going to talk today about two key insights I took from Penn’s talk, because I feel like they’re directly related to writing climate fiction, but I highly encourage you to check out the recording of the Salon and the additional materials that will be in the links.

Here are the two things I want to dive into:

1) the Four Types of Activists and

2) the Eight Stages of a Movement.

These are taken from Bill Moyer’s MAP model (Movement Action Plan), which he developed in the 80’s. I’m sure there are other models and more recent ones, but I found Moyer’s model very helpful to frame thinking about movement building and activism in general. Plus our presenter, Penn Garvin, who has been doing activist work since the original Poor People’s campaign and is currently working with the Pennsylvania Action on Climate group, is still holding workshops with this model. I’d say that speaks to its staying power.

Penn started out asking us what we were most passionate about, not a specific cause or organization or movement, but more generally, what drew us in, what was the kind of work we intrinsically enjoyed doing. Which I thought was a great lens. For me, the thing I’m most passionate about is obviously storytelling, but in terms of what’s always drawn me in—and this predates being a writer—is understanding complexity and communicating that in an understandable way. Even in my engineering work, I was drawn to complex subjects: I love digging in, doing the research, really understanding something from the inside and then turning around and, not so much teaching it, but taking an educator-like role in helping people to understand complex things in simpler terms. Not dumbed down, but in a way that gave insight or meaning or became actionable. Storytelling intersects strongly with this because stories hold complexity really well. They’re a great way to engage people deeply in a subject and the stories themselves are complex enough to hold space for exploring all the permutations.

I remember early on in my writing career learning about “theme mirroring” in storytelling—that’s when you explore a theme, say a father-son relationship, through several sets of characters throughout a story—and I was entranced by that concept. It’s a form of complexity in storytelling and there’s an intrinsic pleasure that comes from the resonance of the theme seen in all its complexity, for both writer and reader.

After Penn listened to all of our passions, she explained there was room for every single one of them in movement work. Movements needed everyone’s talents, not just bodies to run the phone banks, or activities that were often tagged as “the real work”. Penn said movement building especially needed those of us in the arts because the arts drew people in and engaged them, which was a critical piece of building a movement.

That was very affirming to hear, but then she went on to describe the Four Types of Activists, and I suddenly saw an entire lifetime’s worth of work through a brand new lens. We humans like to categorize things, especially the engineers and scientists among us, so this was hitting all the right notes for me.

Penn showed us a four quadrant box labeled: Citizen, Reformer, Change Agent, and Rebel. I’ll explain those further in a second, but she emphasized that no type was any better than another, that all were important and necessary, but that it was especially important to understand which kinds of people, with their particular passions and talents, would fit best into which kinds of roles. If you take a Rebel and shove them into a Citizen role, you’re going to have an unhappy, burnt out activist. Not to mention, when you need the Rebel, they’ve already moved on.

These four types of activists are, again, from Moyer’s Movement Action Plan model, which can also be found in his book, Doing Democracy. These are his definitions.

The Citizen activist promotes positive, widely-held values like justice and non-violence, they’re squarely in the center of society, and they protect the movement against charges of “extremism.”

The Reformer uses official channels to make change—this is elections, lobbying, legal action—and they monitor success, assure enforcement, and guard against backlash.

A Change Agent uses people power—these are the organizers, the strategic thinkers, the people who educate and bring people together.

And finally, the Rebel, which is the activist role most people think about, positively and negatively, as if activism in the streets is the only kind. But it takes a certain type of person to physically go to protests and say No to a violation of those positive society-held values, to use civil disobedience to bring an issue to the public spotlight. That work is exciting but also risky, and it’s not for everyone, but it’s definitely for some people.

Moyer’s framing allows for all kinds of people but he also emphasized that there were effective and ineffective ways to fulfill these roles. If you’re going to be a Reformer, you want to be one that actually uses their power for change, not just promote minor reforms. If you’re going to be a Change Agent, don’t demand utopia or be dogmatic, ignoring people’s actual needs.

Now of course, my mind immediately goes to creating characters, and the idea that these are archetypes that characters can slot into, being either effective or ineffective in their roles, not to mention that there could be characters who understand these roles better than others and can weaponize that, for good or evil.

We writers get up to some trouble pretty quickly.

Real people and characters don’t fit neatly into boxes, but this framework mapped well to various kinds of activism I’ve personally engaged in. At one point, many years ago, when I started attending my local school board meetings and publicizing their shenanigans, kind of like a citizen reporter, I was being a Change Agent—someone who educated and brought people together. When I ran for school board and won, I became a Reformer, working from the inside to make change. Most of my life, I’ve played the role of active Citizen, championing justice and non-violence, getting out the vote and reinforcing core values. I have also marched, but that was always my least-comfortable role. My version of being a Rebel has always been speaking out, using words more than physical protest, although I support protest and understand the role that plays. In a way, my storytelling is my most Rebel activity. I’m still very involved in those other capacities, but storytelling is where I use my words to break conventions and shift the narrative about climate change, shouting No to the violation of our right to live without pollution in our skies and warming in our climate, trying to rewrite the future that’s barreling toward us.

I think a lot of the strife within climate and other social movements can come from one role not understanding the importance of the others. As a storyteller, I write characters into all those roles, and through stories, we can help folks see the relationship between them, what effective and ineffective looks like, and how the different roles can work together. Having an understanding of those archetypes can deepen our storytelling.

Eight Stages of a Movement

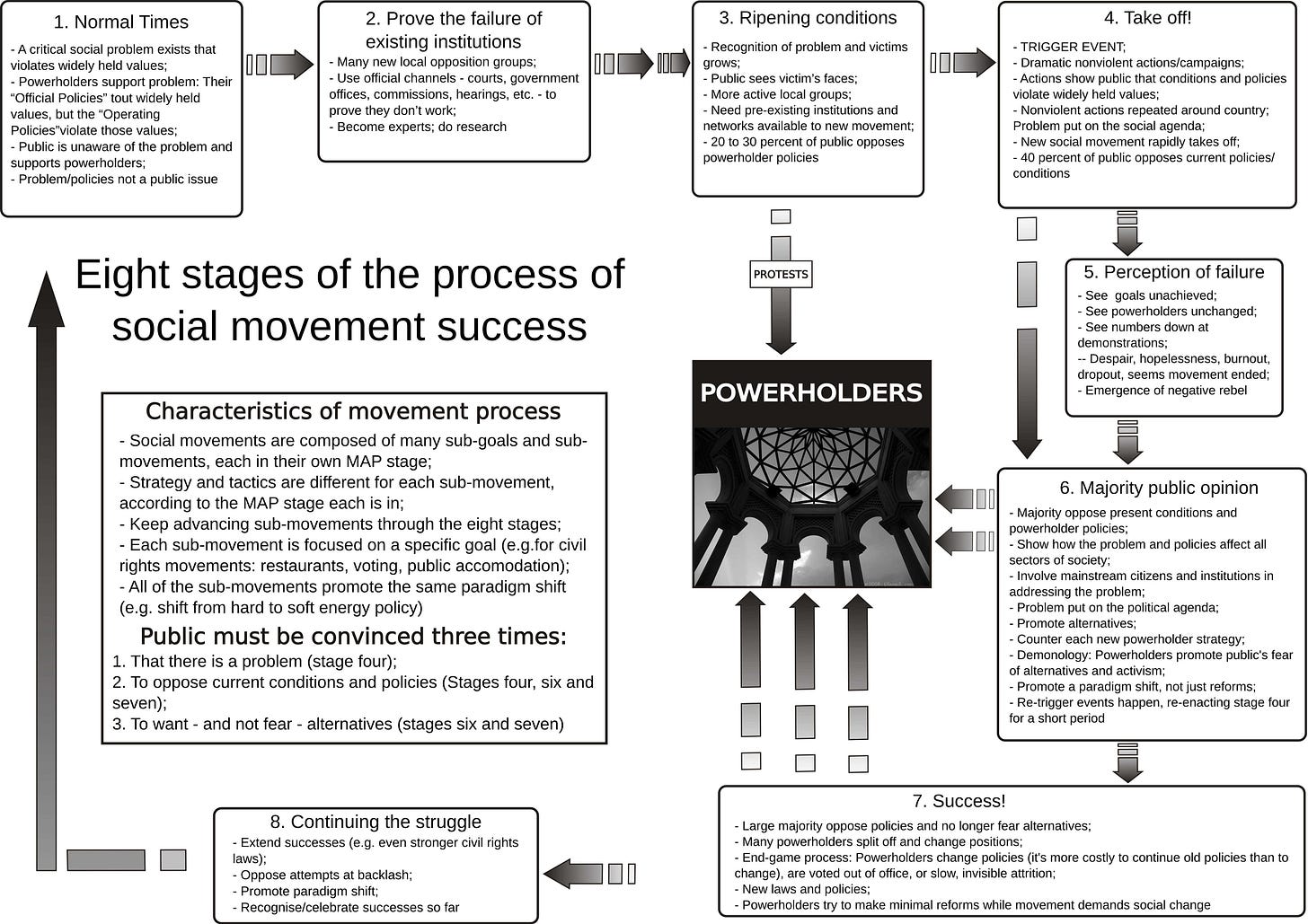

Which brings me to the second powerful piece of Penn’s talk and Moyer’s book: the Eight Stages of a Movement. There’s too much to go into detail with this, so I’m just going to list off the eight stages with brief descriptions and then highlight some key aspects that I think are important for climate storytelling.

Here are Moyer’s Eight Stages of a Social Movement:

Stage 1: Normal Times — the problem exists, but political activity is low

Stage 2: Prove the Failure of Institutions — people grow increasing upset about the problem and the status quo is less tolerable, especially when authorities violate the public trust

Stage 3: Ripening Conditions — pressure begins to build, foundations are laid, the grassroots infrastructure needed to support change is being constructed

Stage 4: Take Off — this is a trigger event, unforseen and unforeseeable, that bursts into the public spotlight, an event that triggers mass non-violent protest and civil disobedience. Note that this is the fourth stage and the movement has been building for some time, but this is something new, vivid and unexpected, but people can mistake it for the entire movement.

Stage 5: Perception of Failure — precisely because the Take Off event is mistaken for the entire movement, when radical change doesn’t happen overnight, there’s a perception that the movement has “failed” but it is really just reaching the next stage. This is a dangerous time, because perception can become reality if people lose faith. Ironically, this stage can happen at the same time as the next stage, where the movement is gaining majority support.

Stage 6: Majority Public Opinion — Activists have to push through their crisis of faith and consciously transform from short-term crisis mode to long-term popular struggle mode, working to gain the support of the majority. This is the long, slow stage of winning the public opinion and then forcing political leaders to abide by that majority that wants to see social change. It is the inverse of Stage 1: Normal Times when injustice is tolerated and reinforced by majority opinion.

The last two stages are Stage 7: Success and Stage 8: Continuing the Struggle, wherein the political class and society-wide institutions have a final stand, trying to stop change, but they ultimately have to capitulate to the success of the movement and then follow-on movements build from that success.

The Climate Movement: Stage Six

Penn Garvin, in her talk, said the climate movement is in Stage 6, and I agree. A majority of the world’s population, even in America, understands that the climate crisis is real and it has arrived. They want the world’s leaders to do something about it. But the process of forcing those leaders to abide by that majority opinion is still very much under way. And the climate crisis is such a huge, globe-spanning problem, that it has many aspects to it, each of which are movements in their own right and might be at different stages. So while the overall movement may have reached Stage 6, there are some aspects that are in other stages. For example, banning Chlorofluorocarbons that were destroying the ozone layer, can be pointed to as a success, an eco-movement that reached the Success stage and resulted in the ozone hole shrinking. By contrast, the recent discoveries of microplastics and PFAS in everyone’s blood are still at Stage 2: the failure of institutions to protect us. But I agree with Penn that the movement writ large is at Stage 6, which is the hardest, longest stage of moving people from passive agreement that change needs to happen to actually implementing that change, politically and societally.

And of course there are always forces trying to push the movement backward.

As a writer, these stages sound very much to me like story structure. It’s also a story of conflict. Even within the climate movement, you can see conflicts between different kinds of activists who act as though we’re at different stages in the fight. And they can easily be right, because there are so many facets to the fight overall. As a storyteller, those conflicts — and how to resolve them to get everyone in the movement to the next stage —are ripe for crafting stories. You could have a character who understands this larger social movement model or one who struggles to figure out where they fit as an activist. You could have casts of characters that illustrate the struggles to get along and work together. You can portray whole communities that are themselves agents of change, inspiring and bringing other people into the movement.

This model isn’t an exact roadmap, for movements or stories, but it gives a framework. You can use it to give structure to your stories or plot arcs or conflicts. Your characters can argue, within this framework, that they should be pushing harder or taking different tactics. Or that it’s time to get fired up and go out into the streets. This framework can be used to help readers—and characters in your stories—see their part and connect their actions to the larger movement.

The Role of Climate Fiction

Lastly, I just wanted to share one slide from the talk I gave at the Sustainability Salon last year. You can find links to the slides and a video of the talk in the notes.

This slide shows fiction, both the hopeful kind and the doomer kind, as one of many influences on the narratives we hear about the climate. Those climate narratives are influenced by science and reality, by activism and real-life stories, and there are bad actors trying to influence the narrative, to stop you, at all costs, from challenging the status quo and moving from passive to active with regard to the climate fight. Fiction plays a role alongside all those other influences, with hopeful climate fiction being under utilized and somewhat absent so far in the fight.

I started this podcast to help readers find those hopeful climate fiction stories and to talk to my fellow writers who are interested in taking the leap to write in this genre. Writing these stories is not easy. We are drenched doomerist tales about the future, especially about the climate, and writing hopeful climate fiction goes against decades of storytelling status quo, just as building a sustainble future goes against our consumerist and capitalist status quo.

The stories we tell and the society we live in are very much linked.

One of the most important things hopeful climate fiction can do is to connect the individual to larger social change. I believe that’s what a lot of people are searching for.

Our stories can help them find it.

Bright Green Futures is a weekly newsletter/podcast. Check out the Featured Stories and Hopeful Climate Fiction lists for further reading. The best way to support the show is to subscribe and share the stories with your friends.

LINKS Ep. 7: Climate Fiction in the Larger Climate Movement

Sustainability Salon page, hosted by Maren Cooke

Sustainability Salon: Hope is a Plant You Can Care For or Kill (Aug 2023) (Susan Kaye Quinn, PDF, recording)

Sustainability Salon: Movement Building (Oct-Nov 2023) (Penn Garvin, recording)

Bill Moyer’s MAP (Movement Action Plan) (The Commons Library, video)

Doing Democracy by Bill Moyer

Share this post