In this episode, I chat with writer Ana Sun about her stories that examine adaptation in the climate crisis.

Text Transcript:

Susan Kaye Quinn

Hello friends!

Welcome to Bright Green Futures, Episode Ten, Adaptation in Climate Fiction with Writer Ana Sun. I'm your host, Susan Kaye Quinn, and we're here to lift up stories about a more sustainable and just world and talk about the struggle to get there. Today we have Ana Sun on the pod. She spent her childhood in Malaysian Borneo and grew up living on islands and is now based in the Southeast of England. She's a Utopia Award nominee, a third culture kid, and has articles in Dreamforge, Solarpunk Magazine, and a couple of anthologies we're going to talk about today.

Hello, Ana, welcome to the pod!

Ana Sun

Hello, thank you Sue for having me.

Susan Kaye Quinn

Oh, it's such a pleasure. I'm so excited to dig in. Your stories are wonderfully creative, and I mean that in a technical sense, that you come up with these cool and inventive ideas, even beyond the culturally rich settings that you create. And I can't wait to dig into that. But I want to start us off with a short excerpt from your story, Soul Noodles, which is part of a new solarpunk anthology called The Bright Mirror, Women of Global Solarpunk. The anthology itself looks fantastic and is billed as imagining life beyond colonialism, corporate greed, and industrialized war.

Your story in particular is so thoroughly about food, which I find delightful and also uncommon. It shows a scarcity of ingredients in this climate-impacted future and how culturally meaningful things could be lost. But you don't stay at that level, you go really deep, which I also appreciate. So first, why don't you go ahead and read the excerpt for us?

Ana Sun

Excerpt from Soul Noodles by Ana Sun in The Bright Mirror: Global Solarpunk by Women:

Wheat noodles sloshed as I scooped them up, with a steel colander from the boiling pot into a vat of cold water, all in one smooth motion. Outside the kitchen window, rainwater gushed with gusto. Sundown must have happened, but the sky only shifted between shades of gray; it’d been impossible to tell the time of day. Most of the city had been underwater since yesterday, but from what I could tell, there had been no incidents. Sampan routes remained in service, crocodile fences held.

Straining the noodles dry, I dipped a colander back into the hot liquid for half a minute. Recipes had been recorded, but interpretations of techniques were just that: suppositions. This was a method Grandpa remembered for preparing these noodles: hot, cold, hot. Boiling water for cooking, cold water for rinsing off the excess starch, then the quick douse back into the steaming liquid to get the noodles hot enough to melt the fat.

I’d made this batch by hand and they looked good; a test strand broke off with a squeeze of chopsticks—I’d timed it perfectly. The seasoning sat ready in a large bowl: fish sauce, soy sauce, peanut oil that I’d flavored with garlic and shallot. The fish sauce I'd made from my own fish, the garlic and shallots from crops within the building, the soy sauce and peanut I’d traded for. A few shakes of white pepper, a touch of rice vinegar. Then finally I picked up the small glass vial that Lily had given me.“Use sparingly, it’s more potent than you think,” she’d warned me when I finally plucked up enough courage to head back to her lab late afternoon.

The milky white goop seemed wholly solid.

“How much is sparingly?” I’d asked.

“Like this, no more than a third of a teaspoon.” She’d pinched her thumb and forefinger together, leaving a tiny gap in between where I could see right through to her eyes. My heart thudded hard, threatening to escape my ribcage, so I forced myself to address the piggy bank instead when I said bye.

The substance smelled like nothing at all as I dripped a tiny amount into the waiting bowl. But all that changed when I tossed in the hot noodles: an earthy aroma arose—rich, salty, and tangy, all at the same time.A few leaves of coriander and sliced spring onions completed the garnish. Once upon a time, we would serve this dish with fried mince or slivers of roasted pork, marinated in a sauce that turned it red. But well, that'd be yet another thing to try re-engineering one day.

I loaded the bowl onto the tray along with some tea and headed to Grandpa's room. The bowl was heavier than the teapot and cup combined; I might have been a clown struggling with a balancing act—except this wasn't funny. The chopsticks rolled to one side, coming to a rest against the teacup. Somehow, I managed to use neither the noodles nor the tea.

Susan Kaye Quinn

The descriptions on this are so rich, especially with the food, but really all the different cultural resonant things that have, that are alongside the food and separate from the food. The main character is trying so hard to reproduce this dish, kolo mee, which I don't know if I'm even saying that correctly, for his grandpa. And you have all kinds of great commentary about how getting the precise ingredients is such a challenge, something that I think in our supply chain vulnerable world, we can now perhaps understand a little better. But I have to start with asking, have you made kolo mee or where did the inspiration of using this particular dish come from?

Ana Sun

I think I write very much from somebody who's diaspora now. I mean, I was born there. I was born in Asia. But quite often, you're recreating memories with food. And so, yes, I have made it. But I don't feel like it's ever going to be good enough compared to what it actually tastes like when you eat there. It's really around the atmosphere we have a meal with. I think I actually wrote this into the text as well. It's very specific to all the other environmental stimuli that you get when it's something like this, when it's a dish like this. So I didn't make it up.

But in many parts of Asia, especially the area where I'm from, migrants have come from everywhere, especially different parts of China. And over the course of several hundred years, they brought with them their traditional food. And this is after quite a lot of trade has happened between the region and also sort of China, ancient China.

They bring with them their traditional food and rituals, and food is very, very strongly tied to identity when you're away from home. And if you're Chinese descent, it's quite strongly tied to sort of clan and the origin you've come from. And even today… so I'm several generations down the line, and there will still be differentiation made between different types of food, despite the fact that we've all acclimatized and we've lived here in this land, on this land for a while.

So every now and again, something gets innovated locally because of the types of ingredients available were different from where people originated from. Kolo mee is one of those dishes that was, as far as we're able to tell, the history traced back to the city I grew up in. And there are several other dishes in different cities, if you like, there's that level of identity we're talking about.

But the problem is most of this kind of history for this thing is verbal. So the trace who actually invented it cannot be cross verified. So there you go.

Susan Kaye Quinn

Oh no, that's great. And I love how it just touches on so many different things: identity, history, you know, the pattern of where people moved from and to, and what they brought with them and what they couldn't find there and how they adapted. It's such a rich context for an adaptation story. It just works so well.

There are many levels you’ve got going on here, but one is just the cooking itself, where cooking is something that you do that embodies your care for each other. So it's like the care work that builds those bonds that is the foundation of any society that is functioning. And you have so many like sweetly tenuous relationships in your stories. You've got unlikely friends and erstwhile love interests where we're very confused about who we are and who they are, and also assigned family, which is what your main character in Soul Noodles is, meaning he's not the grandpa's biological relative. And you barely talk about that inventive social structure in the story. But I am very intrigued. I talk a lot about alternate family structures, not just your usual found family, but like how we could institutionalize that. So I'm very intrigued by that part of it. So can you tell us a little bit more about how assigning works in your story world and what is the motivation for that within the story, but also what is your inspiration outside of the story?

Ana Sun

What's funny is, so many of my stories get several pairs of eyes before I send it to an editor or publisher and when I sent this story to my critique partners, that was like the one word everyone got hooked on. What is this Assigned Family stuff? It's just like the one word everyone made comments on. Even my editor for this particular story, Francesco, remarked on it when he gave me feedback. I was like, woo! And to be honest with you, I haven't really thought about all the mechanisms. Francesco was asking me, Is this an AI-driven thing? And should that be bad? And I was like, yeah, that would be bad because you can't do that kind of thing by computer systems and algorithms. There's so many more nuances that you have taken to account. But I can tell you where the inspiration comes from. How it works, tenuous in my head, to be honest with you, in my head, I kind of assume that people… For example, if you know someone's older, you need someone younger to look after them and vice versa. And at one point that relationship switches. We do this with our parents already in the current world. They look after us, we look after them, or we should. And I know that circumstances, at least in the not so long distance past where immigration is a thing, and certainly I experienced this myself, where you're quite far away from your own parents or from your grandparents, it becomes a thing where you have this gap, now how do you look after each other?

One of the interesting things about the community I grew up with is we have, we call them family friends because it's a convenient term, but essentially we have family that is not blood related, that may have not been related to clans, or just people you've got close together by circumstance, or you have a lived experience together. There's nothing on paper, but you look out for each other. You make sure everyone's okay. I think that's partly where it comes from. So I'm definitely post-rationalizing, just so you know.

That is just my direct experience of it, but at sort of a more societal level…like my grandfather, for example, when he came from China, he came from what I understand was a violent relative and I'm not even sure if they've ever met or maybe somebody they met in childhood and followed as an adult. And so it's difficult for me to imagine what it's like now. But what happens is you see the majority of cases where people were economic migrants, they band together by clan groups where they may have been from a particular area, spoke the same languages or dialect, word choice. They look after each other. They are sort of like associations of groups, clan-based groups, which are kind of more formal community setups, and they have schools for their kids. They have like places for new arrivals who have no family, a place to sleep and a safe place and to be fed and things like that. So it just occurred to me that, as we go through the climate emergency, we have a model that exists already for how people look after each other in tough social conditions where there's very little money, very little resources. What I really like about this way of doing things, it doesn't erode identity and enables collaboration. So I guess that's where that inspiration comes from. So much stuff on just one word, so sorry about that.

Susan Kaye Quinn

I think your comment about how it jumped out at everybody and you get comments back on that, it tells you you're touching a live wire. And I think it's one of those unspoken things where, it varies by culture, but we have some very rigid sometimes definitions of this is what family is and this is what family isn't. But in reality, we have these very complicated systems of care that people come up with in all different situations and across time, because we do want to take care of each other and we want to make sure… okay, if you don't have a grandpa, we'll slot somebody in that functions as the grandpa role. Like that's a thing we do because it's such a core part of who we are as a social species. The need for it is so tremendously deep that we will do that. I see that especially with any kind of marginalized people, vulnerable people, systems, groups of people that are in situations that are more vulnerable, they will do this. They will come up with their own structures. And we need to be open to, like, yes, look, we don't have to reinvent the wheel all the time, right? Look at all these people who have figured out other ways to do this thing we call taking care of each other. And as we go forward through the climate emergency, everything's going to kind of shift, like we're going to have these aging demographics. We're going to have climate migrants. We're going to have a lot of precarity for people in all different ways.

That's one reason why it jumped out to me, and it's also why I have it in my stories too. I'm like, oh, this is like the big thing that we're not really talking about that we need to talk about, because we need more imagination around this and to sort of like normalize it and expose people to it. Look! Other options, people! So I was very glad to see that.

Ana Sun

I think it is so true, because the discourse is still… we still struggle with the idea of a family unit. And some of the doctrine that I think we were brought up with. I think it's probably fair for me to say that reinforces a father and a mother, and there are grandparents on both sides. And when you have social upheaval, that is not necessarily possible. I can think of myself certainly, like you would seek out someone to become a parental figure, to become sort of like a grandparental figure in your own life even if they're not. So I wholly agree, I think it's something that we really need to address and talk more about and be open to different family structures and be okay that it's all different shapes and everyone will be, there will be a variety of shapes.

Susan Kaye Quinn

There will be, and we have to be open to it, but also talk about it enough that we can normalize some of it. Like, Oh yeah, of course, they're gonna have a relationship. It doesn't have to be something that you have to socially justify. Because we have all different levels. We've got the level at which we normalize something with the legal system, and then there's social acceptance, and then there's just like, can I do this and not have mom give me shit about it? There are many levels at which you have to, you know, negotiate those relationships. So super glad to see that.

That's kind of a theme in a lot of your stories, this negotiating of relationships, which I want to get to in a second. But first, I want to switch to talking about Night Fowls, which is another story of yours.

Another very inventive story in the Solarpunk Creatures anthology, where in your story, we've harnessed technology to communicate with animals. And apparently we're using that to keep the peace between warring bird gangs, which I just thought was fantastic. I just smiled through that whole story. But more seriously, both Night Fowls and Soul Noodles are about creative adaptations in a world that's very climate changed. So I want to talk a little bit about that in the framework of the climate crisis, and then we'll get to like, why you actually chose to tell these stories.

When I was speaking to some high school students about writing climate fiction, I framed climate stories as very broadly about mitigation, adaptation, or managed retreat. Meaning that proactive choices could be made by the protagonists or by the construction of the story world, showing people trying to adapt or trying to mitigate the effects of climate change or intentionally moving away from those impacts. So of course there's a lot of overlap between all of those and in the real world, the climate crisis is already here, and our responses have not been very proactive. We are mostly reactive, either we're cleaning up the mess or making small changes but very seldom like actually adapting or preparing for the next disaster. And when there is retreat, it's usually very unmanaged, like fleeing wildfires in Hawaii or the floods in Pakistan. And then temporary displacements often become permanent. Meanwhile, there are those who are unable or unwilling to leave, which leads to a lot of suffering and death. And then there's the whole evil version of managed retreat, where people are forced by violent means to relocate.

So every year we're seeing more climate refugees, both inside countries and between them. And it gets very tangled whether people are fleeing the drought or the violence that was exacerbated by the drought, and whether that was by choice or were they forced to do that. So discussing all of that… I'm sort of like, this is my giant caveat of like, we're not really actually gonna talk about that, but there is a lot of context out there and we could do a whole podcast about that. And we might have to have you back to do that podcast because there's so much to dig in there and a lot of nuance.

But my framework for the students was mostly to just get them started in thinking about possible proactive responses to the climate. And your stories reminded me of this because it struck me that both of your stories use adaptation as a lens for speaking about climate impact. So tell me more about why you chose to write about adaptation.

Ana Sun

I had think about this very carefully because I don't know if I took too much time to reflect on this in the process of writing. Actually I was thinking most of my stories are probably through the adaptation lens because mitigation is something that feels kind of too late and I want us to be able to think about how to be proactive and designing futures, I guess, is the way, the lens, I think about. I sort of have this passion for understanding how the process can help us arrive at better solutions. I guess part of it is to explore the solutions. And as you very, very aptly put, retreat is not well managed, it's not necessarily always an option. But maybe, if I just stop and think about it, I think it's just like pure pragmatism to some degree. Some of it involved in, like you said, in the global south and even the global north, moving isn't an option. There's costs and there's geography. In some places, it's just hard to move from. And mitigation requires systemic action. It's really difficult for us individually to do anything, even though we can try and sort of work through a system, but it's not something that's very easy to do and governments are not fast enough to act.

I spend probably a lot more time reading nonfiction, academic papers, watching YouTube videos about people who talk about having to relocate and move. And what you see is people are attached to places and rarely do they want to move. And you can hear stories like this anywhere from the California fires to the islands in the Pacific. We don't want to move because we are tied to places because of history, heritage. Our grandparents were there, our ancestors were there. It's very, very traumatic. And so I guess part of it is that's why I take that lens.

I quoted Francesco Verso in the article I wrote for Dreamforge, Write the Future You Want To Live In. And I'll just repeat this because it's helpful for me, to remind me.

…he described to me two kinds of solarpunk stories he has read: (1) stories by the more privileged, who can “optimistically imagine hopeful narratives that include cultivating past values of purity and innocence”, where they’ve survived a catastrophe or an apocalypse so they must rebuild a new civilization; (2) stories by the non-privileged who “cannot look at the past without being horrified, and thus must turn to the future to build their identity and space of existence”— where the catastrophe is happening now and they must fight to overcome it, to get away from the experience of daily apocalypses. And by that, he means things as basic as human rights, education and healthcare, just basic needs.

So I count myself as privileged, but I have pretty modest roots. My grandparents were in a very different place. So I guess I write both, and from the perspective of both. But I just feel that the adaptation narrative is the one that's least given attention to and I think that's why I feel like it's a good challenge for myself certainly to write, to test myself to write it.

Susan Kaye Quinn

No, I'm glad that you are. I mean, I feel like… a couple of things I was thinking as you were talking there. First of all, there's an absence of stories about this across the board. So like wide open, pick which aspect of this you want to explore and there probably isn't a lot of stories out there. Which is why I'm constantly talking about how we need more stories written. But this particular lens that you're taking is so great because, in some cases, just survival is the story. That is the story. It's not that you have to have an active protagonist that's going to go out and have an adventure or whatever, like very much not that. We've talked about that a couple of times on the pod. Just surviving is a deeply important story to tell, just in general, but specifically related to the climate crisis.

Within that, I especially like how you are talking about these awkward relationships that we have to like fix and rebuild and we can still make noodles for our grandpa and we can still negotiate with the bird gangs. It's like there's some joy in there even though what we're really doing is surviving. And I think that's an incredibly important story to tell, that we can survive and not just have it be grim all the time.

Ana Sun

Can I talk a little bit about Night Fowls and the inspiration for Night Fowls?

Susan Kaye Quinn

Absolutely.

Ana Sun

There's a number of things. It's based in a city called Brighton, which is not far away from me. Brightonians would know the history of, I want to say 1964, I haven't got my dates right. But there was a local gang fight that's very famous on the beach of Brighton and actually several coastal towns across the UK. It was weird and it was reported, widely reported all across the UK and given the sort of like lens of conflict, it's just two warring, it's not even gangs, it feels like it's kind of two cultural movements that decided they didn't like each other. It's in the local psyche, the local mythology, if you like. When I thought I would write a story about Brighton, I felt like I had to use this. But with birds, why not? I actually wrote a whole blog post around this, so I could probably send it to you later on. For me, it's an examination of conflict. And how easy it is to just call each other names and other the other without any reason why. And so, Night Fowls for me was that examination. But I couldn't help making it slightly tongue in cheek. And I'm not entirely sure why it became a sort of like a mystery structure, but that's what it was in the end. So Night Fowls has its historical roots and inspiration, if you like. And I took the opportunity to examine potentially a different type of governance at a local level. Because I think you need it, to be honest.

Susan Kaye Quinn

Yeah. And just like we need alternate family structures, we need to alternate social structures, which really kind of grow out of that family based structure. And yeah, we knew to explore all that. It's interesting that you're not quite sure why it became a mystery. I find a lot of climate fiction that's of the more hopeful variety often ends up in that space. Like one of the reviews for my series is that it's a gay Scooby-Doo mystery. And I'm like, never would have used those words, but also you're not wrong. So I think there's something about that. It has to do with Heroine's Journey versus hero's journey, et cetera. We talk about that in different pod, but that doesn't surprise me to have that sort of creep in and be part of it.

But it’s so fascinating that that's part of a historical, like a vibe that was in that location already because of historical events. Very cool. All right.

So can I move to my next question that I had here about, actually still about Night Fowls. Your character struggles with their new job as a human negotiator between the animal groups. But the idea being that humans are supposed to be helping the animals adapt to climate change. But even your character questions this, almost like the story is a meta commentary on how we have this broken relationship with nature, how relationships in general are hard, even between humans, much less humans and animals. And we're gonna have to work hard at all of this. And that's definitely resonant with one of the themes of the pod, which is renegotiating our relationships with technology and nature to find solutions to the climate crisis. So, barring a cool technology innovation so that I can actually be a negotiator between the bird gangs, what kind of obligations do you think we have to “meddle in the affairs of nature,” so to speak, in that sort of active sense, especially with climate change disrupting lots of natural habitats, causing extinctions all the time? You leave that obligation kind of open in the story. You’re describing this unique society and who gets included in that society is very unique and interesting. But I'd like to hear more about what do you think is our obligation and how is that going to work out with us having a relationship with nature?

Ana Sun

Yeah. I find this challenging because obviously I don't know if I have a right or wrong answer to this or sort of like a more definite answer to this. In many places it's already too late for a number of species and in many cases we don't actually know how many species we have lost because we don't actually know how many species they are. Nature adapts with or without us so I think it's kind of human-centric of us to believe that we can and should control nature. I don't think it's our place to play God. I think it’s our place to cause less damage. But I think it’s wise to examine what a new balance could look like. And you know, in some parts of our world today, Indigenous communities in particular, we still have knowledge of how we can be part of the ecosystem, to help nature thrive. We aren't just like, you know, any other animal.

I'm not well versed in all the details in specific cultures, but so I speak in general terms, in the same way that some insects may help pollinate, that humans' interventions sometimes help some species in tropical forests. I don't really have details, I haven't cross-verified this, and I like my evidence. So our enemy here is industrialization and capitalism. This notion that we should continually extract from our natural world and profit from it. I feel like our problem is more that we don't actually ever talk about really is that imbalance of power. So I guess in Night Fowls it's also to examine that human reality of what could happen when we very clumsily in the story, to be honest, it's not a solution necessarily. It's a provocation, I suppose. What happens when we try to balance that power? It's a very real change I feel like we have to make, to sort of upend or evolve our current power structures that currently favor the very few.

Susan Kaye Quinn

What we're doing is definitely not working. Like that is how we got to this situation where we're literally polluting the only planet we have that we're living on and killing everyone, including ourselves. So, you know, okay, that's not the solution. Yeah, but coming up with the alternative is hard and partly because it's so entrenched in every aspect of our society, which is why I end up asking some form of this question for almost every guest that comes on, because I feel like, wow, we really need to nibble at this a lot to figure out what is our place. There are definitely Indigenous cultures that have more of a symbiotic kind of viewpoint in their relationship with nature. So there's definitely a place for humans, but it's a specific kind of place. And, you know, there's something definitely to that, but also, how do we get from where we are to that? What does that actually mean in terms of the world as we have it constructed? So I like your little story. I think it's just so great. I hope the readers will go and check it out because it just gives you a little taste, as these stories do, of another way. And I think that's one of the greatest values of it.

Let's see, I had one other question I wanted to talk about relationships and how some of these relationships that you have in the story, I want to call them sweet. Not like they're like saccharine or immature relationships, but that they're awkward. They're sweetly awkward and difficult. And the characters themselves are very uncertain about the nature of those relationships. I like the how you give a very expansive… it's almost like because we're renegotiating all these sorts of roles that people are playing, that we aren't really sure what…What does that mean? What is my job? Well, how do I, you know, how do I relate to this other person within the context of having all this newness going on? I think that's a vibe that a lot of people, especially young people who are coming into this world and going, What the heck? This is so messed up. Forget all this. I'm gonna do things completely differently. Which, you know, more power to them. But there can be a lot of uncertainty there. There can be a lot of awkwardness and feeling uncomfortable.

So I was wondering if those are just the kind of relationships that you're drawn to portraying, or are you speaking to that awkwardness that’s part of the isolation that we have in our society and our universal need for connection, like what's going on there for you?

Ana Sun

Hmm. I think I have the luck of hanging out with some young people, or people younger than me, I should say, and see how they are growing into their worldview. So actually in many cases what happens is my characters struggle with their own relationships to themselves, and that sort of plays out to relationships with people around them. I think if you have a world where you're conscious of your exploitative power, where the economy is inherently gender based, it becomes less about that sort of simple hero-versus-villain dichotomy that we've come to expect in fiction. So in my stories, I do have antagonists sometimes. I've been challenging myself to not have them. In Night Fowls, Violetta, and in another story, Dandelion Brew, that was published in Dreamforge, as Edriel. And in those cases, they seem to appear as antagonists or villains in the beginning, but they're actually not. And I know that some of your stories, Susan, also do the same. And they just mostly hold an opposing viewpoint and is not always the intention to harm. I guess I wanted to think about models of how we negotiate these relationships, when we are trying to be kind. I am fortunate to work with very, very kind people and it's always interesting to see how, you know, even with best intentions, the systems can still really screw us up. And even if we exhibit every ounce of possible kindness to one another. So I guess it's where I like to see how that functions in the story. And also majority of my stories I've realized and one day I stopped to think about it because…I was approached to do a collection and I was like, okay, what are my stories about? And I realized I write a lot about grief, things already lost, things we're about to lose. And I think if we're going to come to terms with climate emergency, it is very much around how we're gonna have to process our grief, deal with it, and act on it, act on the anger that we're gonna have.

So in my mind, my character sometimes, this manifests anger, frustration. It manifests sometimes as a gentle way to tread our place in the world or to cook noodles for a grandfather. So there are different ways of dealing with grief, which I think, almost like repeating myself a little bit, I think we need to get a handle on this a lot quicker than we're probably used to, if we need to figure out how we might adapt and survive.

Susan Kaye Quinn

Absolutely. That whole grief element is such a huge obstacle for young and old. Like, I'm in the old category. I self-identify as older. And I'm old enough to know how things were different. It's not theoretical, some of the losses. And then when I lost my parents, my parents passed away and now I'm the older generation of my small family. How do I communicate this? Do I want to tell them what they're missing? What is gone? Or do you kind of let that go? And how do you process grief and how do you help the younger people process their grief so that they can exist in the world? Cause that is a huge challenge for our younger generation.

I love all that you're doing with your work. Please, please continue to do that.

I think that's a good place for us to start to tie things up, but I also want to hear about this anthology you have coming up that is celebrating the centenary of We by Yevgeny Zamyatin, which I'm probably murdering that name as well, a book I did not know about, but apparently is a book that influenced 1984, Brave New World and also Ursula K. Le Guin's Dispossessed. And it's a charity anthology for Ukrainian charities. So it's very intriguing. I want to like read that as well as all the previous stuff. So tell us a little bit about that and your story that's in it.

Ana Sun

Okay, the anthology is called The Utopia of Us and it will be published by award-winning UK press, Luna Press, and it will come out May this year. We is an interesting book, it's been one that's been on my shelf like forever. I keep an empty library, I keep mostly books I haven't read and so it took me, when I tried to look for it, took me half a day because it's moved with us three times by that point. If you strip away the austere dystopian science fiction world that we have, it's actually essentially a romance, and sort of a Romeo and Juliet a forbidden love, so hopefully I'm not ruining it for someone with that reading.

But there's so many avenues you can explore. Most people would talk about the politics, the autocratic politics, the rules, the strict social codes, but in the book most of the action happened within a city, like a domed city, but we got a sneak preview of the people who survived outside, and obviously I latched onto that. Very little time were given to the people who survived in the wild and the vast outside world that, just literally, I don't know, maybe a page, a couple pages. With my story, I wanted to explore how a troubled character with a love interest might fare in sort of a utopian future society that live closer to nature's rhythms centuries after the city fell. So it is, I don't know, it has solarpunk vibes, but I guess usually I prefer to set my solarpunk stories in a real location on planet Earth. It's one of my very, very few stories that are not rooted in a place. Not a real place, that is. For me, it was an opportunity to examine rituals and culture. So a lot of old science and Indigenous practice that co-exist side by side with touches of very high tech stuff. And there's some engineering knowledge that hasn't been retained, some deliberately forgotten. So I took inspiration from traditional European farming practices, but also this kind of notion of semi-nomadic lifestyle that existed at the time of the Stonehenge. It's quite a lot more anthropological viewpoint in my story that well, I mean, I'll probably always have some of it, but this is probably one where I gave that mostly the focus. For me, it's a chance to sort of examine love and ritual, if you like.

Susan Kaye Quinn

Sounds amazing. Can't wait to read that. And we will definitely put a link. I think the pod will probably go live before the anthology is out, or if not, then soon after. So we will definitely point people in that direction. Exciting.

Ana Sun

Excellent, thank you.

Susan Kaye Quinn

Absolutely. Our whole purpose here is to help people discover these amazing stories. So I am more than happy to do that.

Ana Sun

I should actually say that my story there is probably a really, really small feature there. There are some really wonderful authors on the table of contents, including Adrian Tchaikovsky and Anne Charnock, both award-winning authors in anthology. So I'm just going to get it and read their stories. Like, no, don't worry about mine. It's going to be a great book.

Susan Kaye Quinn

Oh, no, I will be reading the Ana Sun story first, thank you. I will get to those other people at some other point.

Which also, I want to thank you for bringing your other anthology, the one with the global women writing solarpunk, The Bright Mirror, to my attention. I thought I had my radar out and knew the ones that were out there and coming out. And I had never heard of this one. So just goes to show you, first of all, no one can know where everything is. But again, that's part of the purpose here is to bring the stories and the authors together and have an ongoing list. So if people do discover us, they will be able to go back and look at this wonderful collection of stories that we've brought together.

So we're getting towards the end, and I have my rapid round of three questions for you. What hopeful, and this is tying right into that list that we're growing, what hopeful climate fiction have you read recently that you would recommend?

Ana Sun

This question is surprisingly hard for me because I read very widely and I can't actually remember apart from, you know, I always read other stories in the anthologies I'm in. So Solarpunk Creatures, Fighting For the Future, I've got one in there, also Bright Mirror, but I will recommend a book that I've read some of the stories for and the book has just come out. It's a short story collection by Renan Bernardo called Different Kinds of Defiance. So I've read some of Renan's work. I'm a big fan. I think the collection would be fab. Please read it.

Susan Kaye Quinn

Absolutely. Renan was just on the pod, so we are already aware of Renan's work and big, big fans here on the pod. So I love that. And I actually, I love when the people who are my guests know each other outside of their connection here. So that's perfect and fantastic.

All right, what do you do to stay grounded and hopeful in our precarious and fast-changing world?

Ana Sun

Ooh, before I injured my foot, we would regularly walk the south downs here in the UK. We used to walk in the UK, I think it's hike in South American lingo. I hope to do that now, I'm mostly recovered, but being in nature is one of the best things I find I can do for myself. Failing that, we may take a weekend out camping, and failing that, I talk to my plants. Contrary to what people think, plants do talk back just very slowly.

Susan Kaye Quinn

I see you have some plants on the wall behind you. Is that like, what is that, like hydroponic seedlings? Am I seeing that correctly?

Ana Sun

It's just a propagator. Actually, there's been some few victims, not all of them survived, but I need to give them some TLC in the next coming weeks, now that the weather's warmed up. Yeah, it's just a propagator for baby tropical plants. I just wanted to say, we have trouble dealing with loss, loss is really hard. So staying grounded, for me, I sort of mentioned this, accepting, acknowledging our anguish and grief so that we can move beyond that is huge. Taking the long view definitely helps. Just understanding that we're a tiny part of the universe and that each of us have agency to act, that we exist and that is power in itself. Starting with kindness and compassion, which I know you wrote about, kindness to the world around us. So that's how I remind myself. I've got that little things to remind myself whenever I feel sort of trapped or powerless.

Susan Kaye Quinn

That's great. Those little mantras are so important to just sort of reconnect with our own values. It’s like, Yes, I believe in kindness. Yes, I want to affirm the good values of the world by telling stories about them.

But to get back to our last question. What’s next for you? Are you writing more short fiction? Planning a novel?

Ana Sun

I have a commission story that I'm working on and I'm lucky lately where people have tapped on my door and said, can you write this by that time on this theme? It's a different type of challenge and I love it. I like a creative challenge. If time permits, I might put another story alongside that because I've got some ideas that don't quite fit in the same place. So I'll see how I go. Longer term, there is a short story collection on there in the works on the horizon.

I usually have a bunch of things going at the same time and I am writing long form this spring summer. I don't think it would be directly climate fiction because I don't think people read novels for that, unfortunately. But I, having been writing climate fiction for several years, I feel like everything I know, think or feel about our climate emergency would just end up in whatever I write. So I've just sort of given myself a little bit of a free rein to explore.

Thank you so much for having me, this has been such fun.

LINKS Ep. 10: Adaptation in Climate Fiction with Writer Ana Sun

Soul Noodles by Ana Sun (The Bright Mirror: Global Solarpunk by Women anthology)

Night Fowls by Ana Sun (Solarpunk Creatures anthology)

Dandelion Brew by Ana Sun (DreamForge)

Write the Future You Want To Live In by Ana Sun (non-fiction article on solarpunk in DreamForge)

Ana’s blog post about Night Fowls (also on World Weaver Press)

The Utopia of Us (contains Ana Sun’s story, published May 28, 2024) a tribute to We by Yevgeny Zamyatin

Fighting for the Future: Cyberpunk and Solarpunk Tales (contains Ana Sun’s story, The Scent of Green)

Different Kinds of Defiance by Renan Bernardo

PLEASE SHARE

Tiktok, Facebook, Mastodon, Instagram

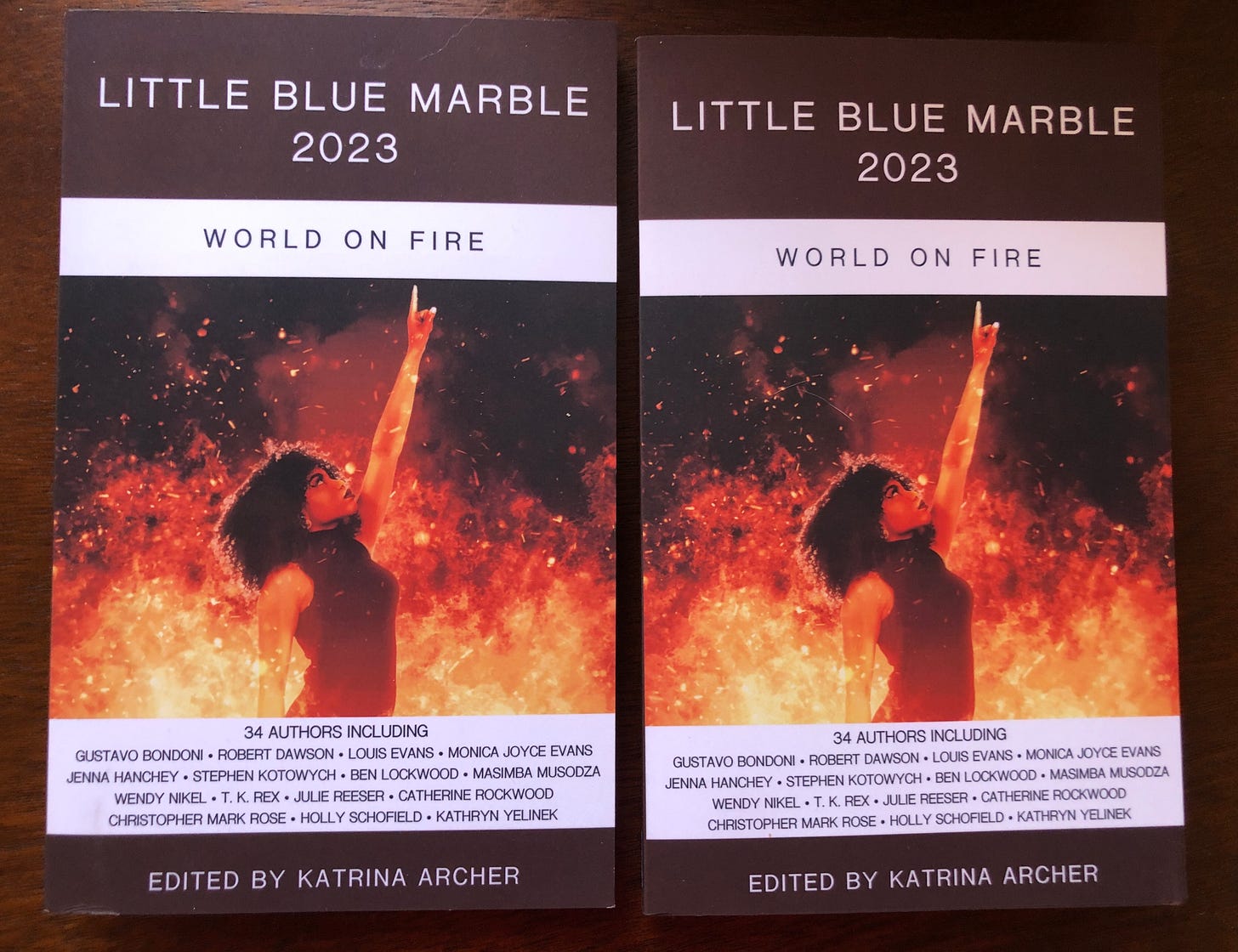

It’s the end of May! I’m giving away a two copies of Little Blue Marble’s A World on Fire, a slim anthology that contains my very short prose-poem Rewilding Indiana alongside a bunch of great climate fiction.

I’ll pick from subscribers, so if you haven’t already subscribed, now’s the time!

Share this post