In this episode, I chat with Author Tashan Mehta about the shapes of stories and how form has to meet function as we tackle storytelling around the climate.

Text Transcript:

Susan Kaye Quinn

Hello friends! Welcome to Bright Green Futures, Episode 16: The Shapes of Stories with Author Tashan Mehta.

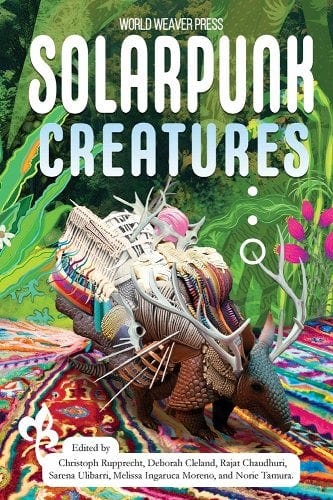

I'm your host, Susan K Quinn, and we're here to lift up stories about a more sustainable and just world and talk about the struggle to get there. Today, we're going to talk with Tashan Mehta, who I discovered through her amazing story, Leaf Whispers, Ocean Song, in the Solarpunk Creatures anthology, but she has short stories in two anthologies, numerous articles, and two published novels: her debut novel, The Liar's Weave, and her more recent work, The Mad Sisters of Esi. I think I'm saying that right.

Tashan Mehta

Perfect.

Susan Kaye Quinn

Which is currently available through HarperCollins India and will be coming out in the US from DAW Books in the fall of 2025. Tashan was also a fellow at the 2015 and 2021 Sangam House International Writers’ Residency in India and Writer-in-Residence at Anglia Ruskin University in the UK. Hello Tashan, welcome to the pod!

Tashan Mehta

Thank you so much. It's such a delight to be here. Thank you for having me.

Susan Kaye Quinn

I am so pleased that you were able to come on the pod and talk to us about your great stories. I can't wait to be in conversation with you about your very interesting work and your thoughts on story structure. But first, I want to introduce our listeners to your story, Leaf Whispers, Ocean Song. This is a short story that spans so much: a love story, an encounter with a deep ocean creature, communication between species and between friends and then lovers. And I'd love for our listeners to hear the lyricism of the story for themselves, if you would do a reading for us?

Tashan Mehta

Yes, absolutely. So I struggled a bit to choose an extract for this reading, because I'm just terrible at choosing extracts. But I thought the moment where the creature, the sea creature, comes out of the ocean and arrives on the beach is very good starting point. Opi is this unknown creature that arrives and sort of changes how we understand our relationship to nature. So this is the moment in the story.

Lu doesn't believe much in beginnings—any event of significance has multiple beginnings if you look at it closely enough. This love story, for example, began when they were five, then began again when Jen walked into the office, and tonight, here, is another beginning, of old and new forged together.

But this beginning has a different significance, for it is also the beginning for the world itself. Tonight, a fishing boat spots Opi in the ocean.

Opi takes seven months to reach the shore. Lu and Jen are huddled at Mae's house, watching it on the laptop. Those huge tentacles whooshing out of the sea. Waves, taller than any tree, slamming onto the beach. Fish, flapping on sand, stunned and dying.There is no language to describe Opi. Pictures of it are so distorted no one can agree on what they're seeing. Sketch artists draw illustrations that are optical illusions, like the Penrose triangle. It's like we’re in Abbot's Flatland, Mae whispers, watching a three-dimensional creature from a two-dimensional perspective. Indeed, marine biologist Margaret Blu would say something similar in her first televised interview on Opi: In all our stories, we assume aliens would come from the sky. We should have been looking at the oceans.

Susan Kaye Quinn

I love it. And you know, I just wanted to throw it out there that it is such a delight for me… one of the unexpected delights of having a podcast is that I can just find a story that I love and just reach out and contact the author and say, You know what? I love your story. I would love to have you on my podcast and talk to you about it. And they say, yes. And I'm like, this is a great perk in my life right now.

There is so much going on with this short story—and it is short; it’s not a long story—but the thing that really stood out for me beyond your beautiful prose is the theme of communication. And there's a lot of miscommunication between Lu and Jen, which is sweet and poignant by turns, but also this vast creature, Opi, singing their message over an impossibly long period of time. And you have that analogy it being alien, but also like almost from a different dimension, as if the creature exists on a different frequency of life than our quick-lived humans on the surface. That communication just sort of resonates in people's souls. And I love that aspect of the story. So I'd like to hear a little bit about what inspired you to create that imagery and what would you like readers to notice about this portrayal of Opi?

Tashan Mehta

I love that you opened this question with miscommunication, because it all started actually in miscommunication. It made me think a little bit about how there's so many layers to how we communicate. You can speak the same language and not communicate what you're saying or thinking or feeling. Either your brain is telling you not to, or you can't find the words. Or if you do find the words, person on the other end has assigned another meaning to the words, than the ones you've given them, and things sort of fall apart.

I was thinking about the complications of communication at this very simple personal human-to-human level. And then I sort of got a bit deeper into it and I thought a little bit more about bodies. How much our bodies play a role in how we communicate, how you're holding your shoulders when you say, I love you, how you're smiling, how you're talking, what your eyes are doing when you're smiling. It's all of these cues that one body to another we're sort of communicating with.

And animals obviously do this on a far more heightened level than we do, right? Body language and posture is so much more important as a whole other facet to language and to sound and how they communicate. And so I thought about that as well as a sort of deeper aspect to it. So when I was sort of building out this great collection, which is in this story, a collection of different, all the different animal and plant languages that are there, I was sort of trying to think of how as a human, you can't just do the sounds. You have to do the body. You have to sort of occupy the physical space that you need to sort of occupy in order to become this being that you're talking as.

And then I started thinking about how there's a whole other different level of communication when it comes to, know, smells, hormones, just our body is operating at a whole level that we know nothing of.

I want to sort of circle to when it came to Opi. If we were to encounter a creature that had seen billions of more years than us, that was far more developed than we could absolutely ever imagine, their language would be so much richer and so much deeper than we could comprehend. It would move at levels we just couldn't piece together because it wouldn't be interpretable just through our mind. And so to me, Opi's language had to sort transcend this box we put language in, where it stays in words, in air, in sound, in assigned intellectual meaning, and move to that level of the body, but also something more than the body: dreams, soul, things we just have no clue about, just the whole, un-understandable part of our world. And so I think what I want readers to take away from it, and what was really important for me to take away from it was… I feel like the world is singing to us constantly. It's consistently telling us things. We just don't have the right ears. We just don't know how to listen. And it was so important to make Opi's language multilayered because you have all these amazing linguists in this story that are just weeping with the knowledge that they cannot touch it. They cannot understand it. It's beyond them.

Susan Kaye Quinn

I just love that so much. And I love all the complexity that you've built into this story, all these different ways of knowing, which is such a deep and complex idea. And I feel like sort of the world is, certainly if you're already a linguist, if you're already a writer, and by the way, there's this funny added meta level where you're describing all these deep, complicated ways of communicating with tiny scribbles on a piece of paper, right? Like it's all going to go through that tiny, you know, eye of the needle to get to the reader, which is again, a credit to you as a writer that you know how to use your medium to evoke those feelings and thoughts. And which is one reason why, when I read it, I'm like, this is just… this is just operating on a lot of great levels and I want people to know about you and your stories.

But so back to this moment in the world, if you're already a linguist, if you're already a writer, I think you are already aware of some of this. And if you start to dig into it, you understand the vast depths of communication and ways of knowing, ways of intelligence, that we're not really accessing with our prefrontal cortex, and that we will respond to in our bodies, we’ll respond to in sort of deeper parts of knowing without really understanding even why sometimes. We need to start bringing that up to the conscious level more.

But I feel like we're kind of going through that as a moment as we have stories like yours that are talking about interspecies communication. And that's been a touchstone on the pod from the beginning about how that really opens up our ability to examine what communication is really about, what intelligence is really about, how embodiment matters a lot in terms of all of that. So I just absolutely love that you there with that.

That kind of leads into my second question that I had: there's a term in botany called plant blindness that I've been thinking a lot about lately. It's this idea that you're not, if you're not a plant person, which I never have been, but strangely enough, I am becoming in the process of I'm rewilding my yard and writing a novel that's full of plants. So I'm doing that deep dive that you described. But if you're not a plant person, you look at plants and you just see like a mass of green, like you're blind to the variety and the peculiarity and the specificity, not to mention the quiet slow motion drama that's hidden in the plant world. And even hidden is the wrong word because it's really plain for anyone to see if you just know how to look and how to access information about what you're seeing. So which is endlessly fascinating to me.

So you have a scene at the end of your story where Lu returns home and she has a moment where… that I think of as her losing her plant blindness. She suddenly sees these other living beings as her partner did and listens to the stories that the 100-year -old lichen is telling her. And that's squarely inside this theme on the pod of renegotiating our relationship with nature. And I think seeing nature, or one step more communicating with nature differently, is part of that.

So in writing this story, did you have that experience of losing some of your plant blindness or were you already like very plant aware and/or why was that an important piece of this story for Lu to have that experience?

Tashan Mehta

I love the phrase slow motion drama of plant life, because it's so dramatic. If you spend time observing plants, they are having like little mini feuds, like they're forming like colonies, fights, countries. It's so dramatic.

I grew up in Mumbai and I don't know if I had plant blindness as much as we only ever saw one tree in a solid tree sort of space. And so every time you saw a tree, a tree was awe inspiring. And I remember feeling very much to myself, if, oh my God, my house, whenever I have it, will have plants, it will have trees, it will be the most magical thing in the world. And then I moved to Goa in 2019, and I moved to a sleepy little village away from the beaches. And I mean, you'll see it in Mad Sisters of Esi, you can see it in Leaf Whispers, Ocean Song, Goa features very prominently. And the reason why that happened is… I don't know if I lost my plant blindness as much as I was whacked into awe. Pure stupefied awe in what nature can be like in its, just in its elemental form. And I don't know if you've ever been to India or ever been to Goa, but the monsoons in Goa is just sheets and sheets and sheets of rain. And I swear to you, it is like every single plant has turned into superhuman plant. I once saw a creeper grow horizontal above the road, supported by just nothing except vibes. It was just going for it. It was just absolutely superhuman.

Susan Kaye Quinn

Amazing.

Tashan Mehta

Absolutely, I saw moss grow out of walls. I saw creatures birth themselves in the corner of my house. I just saw it come for everything structural that we built with a sort of passion that was unbelievably humbling. And I felt very genuinely, and I know this is really silly to people who grew up in nature, but I felt so small. I felt so absolutely wonderfully part of something so much larger and so much more varied and beautiful than my brain could ever comprehend. And so I think I moved into that state of awe with nature and the landscape. And around that time, I read a really excellent book that I'm gonna recommend at the end of this podcast called, The Great Derangement by Amitav Ghosh.

And he talks about two things that I really loved. One is that there was a time in our literature where we decided nature and people were different. Nature was something we were looking at and we were not a part of it. And the second thing he described is there's a time at which we decided nature was still. It was a backdrop. It was a background. It was docile. It was sweet. It was serene. We took out all the tooth and claws and absolute chaos and derangement in it. And we basically, yeah, we nullified it. And ever since then, I've been on this sort of quest to A) resituate us in nature, as in accept that we are a part of it, not apart from it, and B) give nature that same, just give it its teeth and claws back because that monsoon that I saw in that quiet little village, it was coming for and it would tear me apart. Like it was absolutely perfectly happy to do so. I did not matter. I was not in its considerations at all.

And so what happens to Lu, at that end of that story, which is so important to me is she doesn't so much lose her plant blindness as she stops defining nature as the other. What Jen has always been able to do, and Jen is one of the other main characters in the story, who is excellent at non-human languages, excellent at sort of seeing herself as part of the environment around her. Jen has always been able to see herself as having a relationship with Lu and a relationship with the lemongrass plant. She's not seen those two things as different or distinct. And Lu has one foot in that world. She kind of works with languages, she kind of understands it, but she's got one foot out. She's still holding onto structures of how we arrange society, marriage, love, belonging. And so, spoiler alert, when Jen dies, she feels deeply alone. And what I wanted at the end of that story was for her to reach a place where she could look around and be like, how can I possibly be alone? I am on a planet with billions of life forms, all of which are talking to me, all of which are from me, part of me, and all of which I will become when I die. How can I possibly feel separate and alien just because this person I loved is no longer here?

It was so important for me for her to get to that place where she both saw time the way plants see time, but also understood the boundaries of herself as less firm than she previously imagined.

Susan Kaye Quinn

Gosh, I love all of that so much. A couple of thoughts. First of all, that spiritual aspect, I'm seeing more and more of that, whether it's animism, that idea that our boundaries between ourselves and the world literally are extremely porous. You know, we are colonies. We are not individuals in the same way that we really tend to think. You know, I mean, we do have individual consciousnesses, we have senses of self and that is very important and powerful, but we tend to go to absolutes because we like to simplify things and we like to just have it be black or white or this or that and it's like… we are very porous. We are constantly swimming in a world of chemicals and bacteria and other species that have this communication happening on all these frequencies that we're not open to because we put ourselves in this tiny little box of self. And I like that you sort of portray that not just as her having losing her plant bindness, but understanding she's part of this larger world and that losing your distinct boundaries doesn't necessarily have to be a terrifying thing. It can be welcoming thing like I'm part of something because that is that is another deeply human urge to be part of something, be part of something larger than ourselves, where like that experience you described of like I feel so small but that's not necessarily a bad thing. It's I'm small because I'm part of the larger world and I think it's such a huge mindset shift that we have to get to if we're going to understand how to live sustainably in that world. We have to start with understanding that we are part of the world and then we can apply that big brain that we have to figuring out how to do that better.

The second thought I had was, first of all, huge fans of Amitav Ghosh and The Great Derangement here on the pod. We've talked about that several times, so I'm super glad that you are bringing it back to us again. And yes, he had so many great insights in there about, you know, I look at the forest, but the forest also looks back. And we have… there is a relationship there.

Tashan Mehta

This reminds me of a really beautiful book that is too academic for me. I got through three chapters, but it was superb: How Forests Think. And it was a beautiful book because it sort of talks about how the forest is not just the trees, it's not just the plants, it's just the animals, the whole ecosystem knitted together and how that exists in the communication between these different variables of the ecosystem. And how if you're in an Aboriginal tribe and you exist in these forests, you are part of that ecosystem and you learn to read it and understand it and communicate with it in turn. And I loved, I absolutely love what you said of feeling part of a collective is not a terrible feeling. It's not at all. It lifts this burden of you, this desire to be special or believe in, just sort of put all your eggs in one basket of how life would go. And it just opens you up to wonder and awe. And it opens you up to just be observer sometimes, which is a really beautiful place to be.

Susan Kaye Quinn

It is. And Ghosh really got into that… part of his genius as a writer is to open up our perspectives about things like that. And he has this wonderful deep sense of time. You know, a lot of his work is very historical. I actually met him recently here in January, or I'm sorry, March. He came to Pittsburgh and was giving a talk The City of Asylum, is a wonderful organization I support here that supports writers who are persecuted around the world for their writing. And then it gives them safe haven. And then there's a whole community here that's grown up around that literary community. And so I got to talk to him briefly afterwards and ask him about climate fiction… He's a delightful man, first of all, he's funny and, but very deeply insightful and what he was doing in that book… like this part, I didn't expect, the part where the forest looks back at us. I didn't expect that part of it. But it was beautifully integral to the main idea, which is that we as a society are having a failure of imagination when it comes to climate storytelling. We're not able to engage with this and why. What is going on there that the literature world isn't doing it, not the way that we should have. Now this was back in 2016 and I think we've had some progress since then, but still we're very much in the failure of imagination mode still at many levels. And so one of his thesis, I guess, in the book was that, and as you know, but I'm saying this for readers and listeners, is that it's the structure of the novel itself and our imperialist Western hero's journey storytelling style that has trapped us in that box that says we are an individual, we are not part of this larger collective.

You know, so it's integral with that argument of nature looking back at us, but he really brought it home to the literal structure of stories. So I wanted to get us to that because that actually is where I was going to go next in my next question, but like beautiful tie-in. Thank you for that!

So you have this impressive background, awards and residencies. You're a developmental editor and book doctor. You give lectures and participate in some innovative storytelling studies, including CERN's IdeaSquare, which was fascinating to me. And I need to like dive in more to what they're doing there, but it's basically they're, you know, I'm sure you could tell us more about it. And I don't even want to focus on that. I just like, wow, this is really super cool where they're, they're supporting, just out of the box thinking on a bunch of different levels of literature and science and etc. But I'm especially intrigued by your lectures about ideological storytelling and the shapes of stories. So I want to hear more about how you think structure can be bent to reflect the ideology at the heart of a story. And I like that word bent that you use in your description because we're not necessarily deconstructing a story—that's fine, but we can just kind of bend, a little bit to be more reflective of what we're trying to do with a work. So on the pod, we talk about how climate storytelling in particular can require different approaches to structure, telling stories of the collective rather than the lone hero. That's again, one of Ghosh's points. Heroine's Journey rather than the hero's journey, which I've talked about a lot.

And I personally have explored different POVs and structures in my stories, my climate storytelling. So very interested to hear your thoughts about how form meets function and narrative as we're doing this storytelling around the climate.

Tashan Mehta

There's two parts to it. One is what I think Ghosh beautifully articulated, which is the shape of a narrative falls in a intrinsic value system. When you say it's a hero's journey, you're essentially teaching people to see themselves as the center of the narrative of their lives and everybody else is side players.

When you ask if traditional short story writing workshops or writing programs, what does your character want? What is your character need? What does your character need to overcome? You're sort of teaching or stitching into that story, that same sort of idea of focus on the individual, focus on the sort of personal desires of what they need. When you get feedback on a story that says there's not enough conflict, there needs to be more conflict. Conflict is a hard story. You're essentially just saying over and over again, if there's no conflict, there's no interest. If there's no us on them, there is no interest. How do you generate interest? How do you create friction? Friction is how momentum is created.

And essentially, it got to a point in my life where... I looked at all of those questions and they weren't working for the sort of stories that I wanted to do. And I think I realized why they weren't working is because I don't agree that conflict is how all momentum and friction is created. The hero's journey is nice, it's fine, but it's not particularly interesting when you're South Asian because what's most interesting when you're South Asian is how do you be the individual in a collective? With that collective that has a mind, thought process and a historical value that's so much larger than you, right? How you're both singular in your body and you're multiple. You're these histories, these families, these thoughts, these processes that you sort of inherited, all these ghosts sort of standing beside and behind you. They're both superimposed into your body and separate out. That's interesting to me. How do you capture that? How do you negotiate that? How do you talk about that?

So when I was sort of thinking about how do we sort of shift our attention? Structure, to me, was the heart of that answer, because structure is how you shape the understanding of a narrative. Structure is how you take someone from point A to point B, and therefore your structure is also determined by what you pay attention to, right? What you decide is the highlight point, what you decide is the break off point, what reader expectations you're frustrating, what you're fulfilling, what new ones you're sort of building. So the reason I say bent is if you think of it as a wire, we have this like same shape that's been sold to us as the correct shape story. What happens if you take the same wire, but you make a squiggle out of it, or you sort of change it to sort of account for different value systems, account for different ways of looking and different centers of attention and power.

And that sort of brought me to the second part of this, which is different ways of looking. So if you take an apple, you can look at an apple front on, can look at it from the side, from the bottom, from every different angle. And each different angle will change how you view that apple or understand that apple or write about that apple. And stories are the same. If you see that story as a singular object, where you approach that story from transforms how you do that. And that's why you have different modes of writing, right? You can write as a dream, you can write as a diary, you can write as a play, you can write in different forms, all of which that is taking that simple storyline and sort of highlighting the bits they want to highlight that work best with their medium. So I think I'm more and more curious about how we bend the traditional shape of stories, especially because those traditional shape of stories exactly as Ghosh pointed out was created. The novel is not a form that has existed forever. It literally came up at about the 18th, 19th century. So it is a form that has become and has just existed now that it's become the absolute. And the whole point of the novel when it was born, and I love this course that I did in my undergraduate, is that it was supposed to be a carnivorous form. It took from poetry, took from epic poetry, took from plays. It took whatever the hell it wanted and did whatever it wanted. And then it just sort of turned out like a Frankenstein, like monster. And we've forgotten that. We've sort of crystallized it into this perfect arc of what good stories should look like. And I just want us to start interrogating that a lot more, especially as you've pointed out, for climate fiction. We have to interrogate how we relate to the whole world. And in order to do that, we absolutely have to interrogate the shape of our narratives.

Susan Kaye Quinn

Yeah, absolutely. What you're saying was making me think again about how science fiction really struggles with this even more, even though a lot of climate storytelling takes place pretty strongly inside the genre of science fiction, we're trapped in that form in that, whereas literary fiction has a lot more permission from its readers to experiment with form. And what I'm seeing is that in science fiction, in short science fiction, there's more permission to experiment with form. And so now you can do more climate storytelling within science fiction in short form. And it's kind of trapped in there because that's where the permission is to experiment with form. I just actually, speaking of not just form, but point of view as being such a powerful way to shift, you know, bend your story.

I just finished writing a short story that I just sent off for the first time, where the world has people turning into plants. They go to the light. They basically become a plant and it's only like one in a hundred, but it absolutely breaks the world. And so the story is about this woman whose partner does that, who goes to the light. And in the beginning of the story, she tells the story as, you know, there's me and there's my partner over there. She does this, she does that. So it's like a first person in her point of view, but she's sort of third person with her wife. But when her wife turns into this other state of being, this human-plant hybrid and roots in their garden, I changed the POV to being you. Now I'm talking to you and it's I and you and I and you. And so that POV shift is so funny. All the critique partners, all the feedback that I got back from it was, wait, you changed, you shifted. Why did you do that? Oh, it's because the relationship changed. Okay. I'm not really sure I'm comfortable with that. I'm like, That whole journey that you just went through is exactly, exactly what I want you to experience.

Tashan Mehta

I love this so much though, because it's such a simple change and it's so telling on how we can position the reader. And I really love what you said about readers and permission, because often when you have a novel that is carnivorous and does what it wants, people think it's a bad book because that's a structure they've been taught, right? And that's so interesting to me because I think it's not so much writers being experimental. There's a necessity for readers to see enough of this fiction and learn that it wasn't an accident. It wasn't a bad creative choice. It's not because the writer doesn't know any better. It was done on purpose. It was done to make you feel something that is not in line with what you normally feel in the shape of a story.

Susan Kaye Quinn

And everyone who gave me that feedback, they're like, well, you need to smooth out that transition or you need to change something about it. And I'm like, but not a single one of you misunderstood. Like every single one of you understood what had happened. You just were uncomfortable with it. And that's okay with me as a writer. But yes, this whole idea that we need to, we need to change the expectations. And the only way to do that, is to get more of these stories… I mean, this is essentially why I'm doing the pod: to try to get more awareness of these stories out there for readers, more permission for writers to say, Hey, you're not alone. We're all like struggling with this. How do we grapple with climate storytelling? Let's talk about that. Let's get people like yourself who are doing just like beautiful, brilliant work. And, challenging those, you know, things that say this is wrong or bad or whatever, not the way. This is not a story. I've literally had people tell me: this is not a story. Like as if, as if it's not words on a page telling like very much a story, cause it doesn't fit in that box. And it's so, gosh, we have a lot of work to do. I understand why, whenever I look at that, like we can't even tell stories about this? Really speaks to the struggle that we're having with thinking to a future that's better, where we adapt, where we, you know, take positive action rather than just let the the thing happen to us, which is a lot of the storytelling will be about that. It will be that more passive thing, but I also think we have agency here. We are gardeners. We aren't just passively observing the forest too. You know, so how do we learn how to be gardeners again?

We're going to talk about your story that is coming to America that you've already written and published in India, The Mad Sisters of Esi. Am I saying that right, Esi?

Tashan Mehta

You said it perfect the first time. Also, I made up the word, so technically everybody can say it however they want, but still.

Susan Kaye Quinn

Okay, I shouldn't second guess myself. All right, so I want to talk about that book, but I also want to follow up a little bit later about just like what your plans are for climate storytelling, because I think you're really getting this and I hope you're going to be doing more work with that.

But let's talk about Mad Sisters of Esi first, coming to the US via DAW Books in fall of 2025. Now I actually went on Amazon and thought I was going to be clever and try to order it from India. And US listeners, it appears that you can order it from India. HarperCollins India says they will ship it to you in the US, but Tashan tells me that no, that doesn't actually work. So the book never arrives. So don't be fooled. You can't actually get it yet. You will have to wait for DAW Books to release it in America in the fall of 2025, where I really hope it will get a lot of circulation because it sounds amazing.

And I'm absolutely intrigued by the story about these two sisters who are the keepers of the whale of Babel living literally inside the whale. And I'm going to read a tiny excerpt here for listeners so that they can see how cool this is.

So imagine the whale of Babel as made of three materials. The first is a more traditional material, close to what we know as ‘matter’. This is a dense fabric that retains the shape it is given and is the essence of the heft in the whale. The second is a more pliable material, capable of changing its form. Professor Uoe calls this fabric ‘wish-giving’ and is likely responsible for the formation of the chambers within the whale.

The third material, of course, is the fabric of time.

Susan Kaye Quinn

Yes! I love that so much. I can't wait to read this story. So tell me about the story, what readers can expect from it in terms of genre and tone and form. And also I'm curious if you have in this story any themes of climate or the environment.

Tashan Mehta

It's a really hard story to describe. I just generally say it's a madcap joyous novel of like two sisters moving across three landscapes. It features a festival of madness. It has a museum of collective memory and I essentially wrote it as our love letter to madness. Form-wise it just does whatever it wants. It took four drafts to create this and you can really tell because it does whatever it wants. This is a book that was very determined to be exactly the book it wanted to be on the page, irrespective of whatever I told it. So I just went with it. It feels very outside of me, which is why I love it so much.

It actually, it features a lot of climate conversation, but not so much directly as much as indirectly. I was talking to you a lot about Goa and how I felt when I first went to Goa. Mad Sisters of Esi was conceived and written and thought up in Goa during that time when I was reading Great Derangement, when I was looking at nature, when I was sort of accepting that we are part of it. And what it features very interestingly is landscape as family. And it also talks about or explores different forms of consciousness. And it also interestingly circles around exactly what I was talking about with this being South Asian. What does it mean as an individual to belong to a collective? And what does it mean to write as a collective? How do you capture the sort of tonal nuances of what it means to be a we instead of an I? So these are all those very similar themes that the book is sort of exploring, moving through, sort of trying to understand this singular versus the plural and how we sort of relate to ourselves and the connections and the people that we have in this plurality of not just the collective but also of the cosmos which is so much larger than ourselves. But essentially it's just a madcap novel that does whatever it wants. It's a lot of fun.

Susan Kaye Quinn

I love that because your madcap novel is going to sneak in sideways and do some deep work on people. I like that subversive nature so, so much. And as you were talking, I was thinking about, you know what? This is going to be how it goes for a lot of our climate storytelling in the future because climate is just going to be part of our world and we're going to have to start doing that deep work of shifting our perspective.

And sometimes your stories, you know, they are climate stories, but they might not, you know, scream climate story explicitly. And that's okay. It is also okay to scream it explicitly because we need to do that as well. But I love the subversive nature of any stories that are doing that kind of deep work, that challenge work of the collective storytelling, the shift in perspective, that anything that is going to get us to think differently and plant that little seed in our minds that later on… your big brain can now connect the dots yourself about how, like, that's a better way to be or a more authentic way to be in the world. Which I think is what a lot of people, especially when we start talking about spirituality and the contex, Who am I in this world that is changing all the time? And how do I exist? How do I keep going? How do I react to the onslaught?

I took this one course which is called Alchemize. It was through Green Dreamer, which is another podcast, but they did this sort of series of almost like meditations on our place in the world. And one of the episodes had this concept of Long Body. So you have your body that exists right now. But if you think about you in a prior time, you were a different person, but you're still connected to that body. And then that body came from two other bodies who are connected back in time. And so there's this long body through time, and it also goes forward. You're a good ancestor, hopefully you want to be for your descendants, and placing yourself as a long body is a way of embodying that connection through time to community. And that concept is so sticky. It's stuck in my brain, and it is a seed that got planted. And now I'm like seeing that idea everywhere.

Tashan Mehta

It's beautiful. That's exactly what I'm dealing with in Mad Sisters of Esi. I hadn't heard of this term, but it's exactly it. Because if you think of a body as well, it's a brief moment in time, whereas a long body moves throughout a swath of time. It sort of carries you forward. And I'm really, I'm so fascinated with, I think there was a poem that called it the time of insects versus the time of stars. And I find that just absolutely gorgeous. So yeah, no, thank you for introducing me to the concept. It's great concept.

Susan Kaye Quinn

I need to go look with Green Dreamer and see if they've made public some of those concepts. There were some really great stuff in there and I probably need to do a whole podcast about some of the things that I pulled from that, so people can find it. At the ends of my episodes, I always put a huge list of links so people can track down more information to your books and whoever we're highlighting for the episode, but there's always stuff that comes up during the episode that I like people to have a chance to go find.

Okay, we're getting towards the end, which went insanely fast, but at the end I have a rapid round of three questions that I always ask. So we'll go through that and I want to dive in a little bit deeper. I'm glad we have a little bit of time to explore.

But first, what hopeful climate fiction have you read recently that you would recommend?

Tashan Mehta

Okay, so I'm going to add a caveat here and say that hopeful is being defined as anything that gets us to think differently in relationship to our world. So I two recommendations. One is the Great Derangement by Amitav Ghosh. The second is Latitudes of Longing by Shubhangi Swarup. She's an Indian author. It's published in the US as well. And it's just an extremely strange novel along a fault line and the different areas and geographical places along that fault line and the different communities and places in it. It's a fiction novel. It's absolutely beautiful. It talks very deeply to our connection to the land and to the earth and how we are formed by it. And I think it's just a really gorgeous book to read. So yes, Latitudes of Longing by Shubhangi Swarup.

Susan Kaye Quinn

Sounds amazing. I can't wait to check that out. And I'm glad it's here in the U.S. so I won't have to wait, like I am for yours. Okay, the second question is a little more personal. What do you do to stay grounded and hopeful in our precarious and fast-changing world?

Tashan Mehta

That's a really, really good question. I think to stay hopeful about my life in the future, I look at the people I love and I hold on to the reality of their bodies, the reality of their smell, the reality of moments with them. Those feel tangible. Those feel like things I can hold on to rather than like visions of what I want my future to be like. And they never fail to fill me with surprise and joy. What I do to be hopeful about the climate, because I think that is actually a very pressing question in this day and age is I look to the landscape in which I live, which in this case would be Goa, and I see how I can contribute as part of a collective to Goa. Like, how do we make all the environmental factors? How do we volunteer our time? How do we contribute? How do we change? How we do waste? How do we basically take care of our little patch of the earth? Because sometimes when I look the biggest scale, it's overwhelming and it's scary. And all I can do is sort of anchor myself into this moment, into the reality of my body and where I live and go, okay, but I have the power to do this. I know I have the power to do this and act.

Susan Kaye Quinn

You know, again and again, when I ask people this question, I hear, Go local. I hear touching grass, like literally rooting in your community and finding what can happen, what can change right here, right now that I can touch and feel and connect to. And I can personally attest to that. I've been doing that for years and it is literally grounding. It is literally in the word that you are going to your patch of the earth and fixing and healing it there. And it's so powerful. It's such a great concept. And I keep hearing different varieties of it for everybody has their own way because every patch on earth is different. So I'm sure that the challenges in Goa are going to be different than the challenges in Pittsburgh. And yet we will have a ton of similarities as well. And so it is this kind of interestingly complex connection where we're all kind of do it, but we're all kind of doing it differently and separately, but we kind of bond over the idea of doing it.

My thing tonight, in fact, literally I am hosting a meetup in Pittsburgh of solarpunk enthusiasts. It's like a social club almost of people who are interested in solarpunk. And this is keying off of a solarpunk conference or expo that was hosted not by me, but like the several nonprofit organizations in the city had gotten together, this is the second year they've done it, and this time I got smart and took down some emails from people who are interested in connecting because one thing we don't always do is connect. And you know, there are people who… it is a classic of the modern world that we can be around a million people and yet feel alone… because we're not connecting with the people that we care about or that share our values or just have our similar interests, you know, and finding those people and making those connections. I'm like, let's meet, let's just have a time and a space where we can just get together and talk because we're all into this kind of thing. And I'm very curious to see how goes tonight. There's a bunch of people signed up and it's like the kind of thing where if I hadn't set this up, it wouldn't exist. Like this, I've been here for three years and nobody else has done this. Sometimes it takes a little bit of initiative to start something, but most of the time, there's already people doing stuff in your local area. I'm constantly discovering new people doing amazing things. So you don't usually have to go out and start something. You can just join up with what people are already doing.

Tashan Mehta

I love what you said about people doing amazing things. There's just so many people doing amazing things. And then you meet up with them and you're just like, wow, I didn't know this existed. I didn't know I could participate in that. No, I do agree that connection is really important. And because you can feel alone in a crowd and it's important to find people that make you feel part of something very much. And I'm so glad you're doing the meetup. I hope it goes well.

Susan Kaye Quinn

Thank you, I hope so too. I'm very excited for it. And like anything else I do… I do a lot of, Hey, let's just try this kind of thing. That's who I am in the world. I'm going, I'm a starter. I start things and then we just kind of see how it goes. We plant the seed and we find out and sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn't, but we always learn something from it. And so that's part of my joyful existence in the world is to go start things like that. But I always caveat that because I know not everybody's like that. I'm like, okay, you don't always have to start things like you can just do. There's somebody else who started it and you can just like show up. That's also an option.

Okay, so this last question that I usually ask is just sort of boilerplate. What's next for you? Are you working on another novel? Can you tell us about it? But I specifically, I'm just going to put in a bid for you to write more climate fiction stories, because I just so enjoyed that one. And it does sound like you're doing that deep work in probably all of your works. But I do want to hear more about what you're actually working on now, and can we expect some more climate fiction short stories, novels from you in the future?

Tashan Mehta

So I'm currently working on another novel, working very loosely because I'm a very slow writer. It's currently set in Bombay in an alternate sort of reality. I call it my Bombay Grimm's Fairy Tale. And it has that same sort of connection to nature. But again, with my awe at the center as always, right? More, it's just that this complete sort of humility that I feel when I think of the trees and the nature around us and how it shapes our landscapes.

I have been toying with the idea of doing more climate fiction, but I feel, not when you feel like you don't know enough, when you feel like you want to be more knowledgeable to bring something new to your story and sort of deepen that. So if hopefully over time, if I develop my understanding and I develop my sense of relationship to nature and I have something… important or new are all such loaded terms, but something that I feel is worth saying. I definitely see myself moving back towards climate fiction. But I don't want to be one of those people who adds noise because it's so vital in climate fiction right now to do innovative things with it. Because when people do, when climate fiction's done well, it really changes how people understand themselves. And I want that space for the readers to discover those sort of forms that do that for them. Whereas I don't right now feel like I have anything interesting to say. Hopefully one day that will change. Touch wood.

Susan Kaye Quinn

Oh, I have complete confidence that whatever you say will be interesting and whatever you're drawn to say will be very interesting. I very much look forward to that.

It also touches a little bit on something we talked about in previous pod about what holds people back from necessarily writing climate fiction. And that feeling of… I don't think this is precisely what you were saying, but kind of is adjacent to it… where we don't feel like we understand enough because climate is so big and so complex and there's so much science and it's hard to like feel competent to speak to that unless you're already a climate scientist. But even then, like I have a PhD in environmental engineering and I have to do a ton of research for every story I write. I mean, yes, I have some background, so that helps, but, I encourage people to take a little bit of a leap with that because the other piece of what you said is so, so important that we are breaking new ground. There's a real dearth of these stories. We have a great need for them. And that innovative work is what we need to have. And that is not necessarily having to do with the ice sheet on Greenland. You know, that has to do with our long body experience through this time and how we adapt and how it changes who we are to be alive in this timeframe. And I think that is just solidly in the wheelhouse of most writers, because we also are existing in this timeframe. Like that is our job, to imagine and interpret the world for our fellow humans from our unique lens. And you have such a beautiful way with words. I am super looking forward to whatever you get called to write.

Tashan Mehta

Thank you. I fully agree with you, by the way. I do think climate change isn't theoretical. It's very much our lived reality. We're seeing it every single day. And writing about your relationship to nature is just… it's part of who you are. It's like breathing. It's like having a relationship with another human being. It's very much front and center. So I do very much agree with you there.

Susan Kaye Quinn

Awesome, I love it. Thank you so much for being on the pod today and sharing your works and your wisdom. And I look forward to when your book comes out next year.

Tashan Mehta

Thank you so much. It was such a joy, Susan. Thank you so much for having me.

LINKS Ep. 16: The Shapes of Stories with Author Tashan Mehta

Solarpunk Creatures (with Tashan Mehta’s story, Leaf Whispers, Ocean Song)

The Great Derangement by Amitav Ghosh

How Forests Think by Eduardo Kohn

Latitudes of Longing by Shubhangi Swarup

Share this post