In this episode, I chat with Grist Editor Tory Stephens about Imagine 2200, Grist’s hopeful climate fiction contest, and how envisioning the future is an important climate solution.

Text Transcript:

Susan Kaye Quinn

Hello friends!

Welcome to Bright Green Futures, Episode Twelve, Building Movement Through Hopeful Climate Fiction with Editor Tory Stephens. I'm your host, Susan Kaye Quinn, and we're here to lift up stories about a more sustainable and just world and talk about the struggle to get there. Today, we're going to talk with Tory Stephens, who is the Creative Manager of Climate Fiction at Grist and runs Grist's Imagine 2200 contest, which has published many of the writers we've had on the show so far.

Hello, Tory, welcome to the pod!

Tory Stephens

Hi, thanks for having me.

Susan Kaye Quinn

I am so excited for you to be here. I am a huge fan of Grist and Imagine 2200, for years, well before I actually had a story in the contest. And I can't wait to talk about the great work you're doing with that. It is so incredibly well aligned with what we're trying to do here on the pod, using the power of story to build a better world.

But first, a little background for our listeners. Grist is a nonprofit, independent, media organization dedicated to telling stories of climate solutions and a just future. I discovered Grist in 2020 when I started writing climate fiction in earnest. It's easy to find disastrous news about the climate, either predictions or increasingly just the reality outside our windows. But for my stories, I was researching solutions. And Grist's relentless focus on narratives about how to fix the climate crisis wasn't just a treasure trove of information. It was an incredible relief to read about all these people actively engaged in the fight. So that discovery was actually one of my first insights into the power of these stories, albeit of the nonfiction kind.

So shortly after that, after me discovering it—Grist had actually been around for a long tim—but I finally got a clue. And shortly after I discovered this wonderful resource, Imagine 2200 was launched, and I was absolutely giddy because here was an actual contest in the very thing that I was writing, hopeful climate fiction with a very strong social justice lens. And at that time I hadn't yet connected with anyone else doing this kind of work. We're kind of scarce on the ground even now four years later.

So here's the description of Imagine 2200 for our listeners:

Imagine 2200 engages writers across the globe in envisioning the next 180 years of climate progress. Whether built on abundance or adaptation, reform, or a new understanding of survival, these stories serve as a springboard for exploring how fiction can help us build towards a better reality.

I think the contest does incredibly important work simply by existing, not to mention like the stories that it actually generates and then publishes. So let's start there. I believe you came on board with Grist in 2019 and Imagine 2200 launched in 2021.

So tell us about the genesis of the program. Where did the idea come from? What obstacles did you face in getting it launched? And just tell us the story behind the stories.

Tory Stephens

Yeah, it's actually a really interesting story. So I will tell you, when I first started at Grist, I was not in the role of the Climate Fiction Creative Manager because we didn't even have a climate fiction outfit at Grist. I was hired to help bring together and solidify a group of folks that we brought on through the Grist 50 list. So Grist has this list that's like, you know, Forbes 50, but not focused on capitalism, focused on sustainability, climate solutions and climate justice, that's called the Grist 50. It's been produced for six years. There's like 500 people or so on that list at this point, maybe at seven years. And those folks come from the world of climate justice or climate solution. So scientists, politicians, activists, leaders, all different folks and really a large cross section where you get to see all these really great solutions, whether they be a more societal shift that needs to take place, like the Land Back movement, or something that is like algae eating plastic. My role was actually one of the coolest titles, I think—or I liked it as a title, because I love this one now—but it was network weaver. So I was the network weaver for all those people.

My goal in job was to help bring those people together, connect them. We used to go to retreats and talk about all these rich things in the climate solution space and climate justice space in a private setting so that people could kind of be themselves, get to know each other and have this cohort of people that are jazzed up and really just trying to figure out the climate crisis from a variety of angles.

And so I did that for a while. And it was actually at one of these retreats that we were holding here—I live in Massachusetts and we just happen to have one in Massachusetts—and at the end of the retreat… and I had known earlier that the founder of Grist, whose name is Chip Geller, he had put a bug in my ear that he thought climate fiction was something that could be brought to Grist and would be quite interesting to bring because of the story aspect and how it reaches people that just aren't so much into news. Or maybe even the person who likes news and also likes fiction. Like there's a lot of those people too. We're not just these kind of like siloed people. So at the end of the retreat, Chip said, I want to do one last thing. I want everyone to pitch. Like the whole goal for them to pitch was something new that Grist could start doing that either adds on to the news we do, could be like a new newsletter, whatever they want to dream of.

What's something new and exciting that Grist could do? So everybody went into their small breakout groups. You had five people per breakout group and each person had an idea and then they had to pitch it to the group and then the group had to decide out of their group, what was the best idea? So there was like four pitches that they gave in front of the whole group.

And one of the pitches was that climate fiction should be something that Grist should do. And that group was very energized and their presentation was about how all the ways that they thought that it would be good for Grist. Like they kept listing things like: you already have people that deal with the words, you have editors who can edit, you already have an audience that loves to read, and you know that they like climate as their main topic because you're a one issue site.

I mean, we had talked about this internally, but there was just a lot of back and forth, and just having this group kind of say—without us coaching them, we never said like, hey, by the way, one of the things we want you to pitch is climate fiction—no, they came up with that on their own. And so we left with that.

After that, it was, instead of thinking about should we bring climate fiction to Grist, let's do it.

But like what type of climate fiction we should bring to Grist was the question and how. Like there was no idea that it would be a contest. There was just an idea that, you know, hey, we're going to do climate fiction. In fact, we had contracted with Andrew Dana Hudson, who is a climate fiction writer. I think Paulo also, I’m going to butcher his name, Paulo Bacigalupi.

Susan Kaye Quinn

I can never pronounce it properly either.

Tory Stephens

He was a judge of ours, so I should be good at that. But I'm not. So we actually had two stories living on our site beforehand where we were showcasing climate fiction. (Readers: see show notes at bottom.) But we had never thought about bringing it in a bigger way until then. And so while we went back and had internal discussions, and we kept having these internal discussions around: what kind, how, should it be like a monthly newsletter? To be honest, I still can't remember where we fell upon, like why we decided a contest. I'll try to rack my brain as we continue talking, but I can tell a little bit about the story about how we got there, which I think is actually quite interesting.

So it started to look like I was going to be charged with being one of the main people bringing this to Grist. And one of my asks to the senior team and the folks at Grist who manage this organization was that if I'm going to do this, I want to have another retreat that is solely focused on climate fiction. This other one was about like bringing people together so they could meet each other and kind of network and get to know each other's climate solutions. So they have a better view of the different climate solutions that exist in the world. And so, I went back to the same group of people, the Grist 50 folks, and we curated a group of people that we thought would bring a very diverse set of ideas from the walk of life, like where they're from as a person, their positionality, I guess I should say, diversity. We brought a good amount of diversity, intellectual diversity, and then diversity from folks' sexual orientation, their gender, their race, class, those kind of things. We were really considerate of that so that we could have a really wide sweeping discussion at this retreat.

That retreat was supposed to be in person, but then COVID happened and it was quite complex, like we were pretty deep in the planning of this retreat. Every time we did retreats, because we weren't like masters of retreats, we would work with folks who, that's all they do. So we would co-design these retreats with this team and then have this really nice event for these Grist 50 folks. It was a part of the package that they got for making the Grist 50 list. And so one of the gentlemen, his name's Adam Burke, he's from Maine, he's a really great facilitator. He was at the table with us and he was like, you know…so the goal was we wanted to use visioning, you know, collective visioning experience to get people's ideas out of their head and onto the paper and onto the whiteboards and onto stickies and kind of mine—and we told them ahead of time, we weren't doing this in extractive way, we were doing this in a kind of generative way. We said that you're going to help launch something at Grist that will be new and exciting and climate fiction and people were in. And so we invited them. They knew that it was about climate fiction. And when we were designing it, one of the facilitators, Adam Burke said, You know, I have a background in games, I love role playing games. Why don't we mash together visioning, collective visioning, the old world kind of wisdom techniques to kind of like vision your future and do that collectively, but with game dynamics that are like role playing.

At first I was like, wow. I immediately thought, even though I'm not a person that

comes from like a D & D background, Dungeons & Dragons or any of those. I played video games in my life and I played board games, but I never got into that kind of games where it's like you might be playing for a couple of days and you might dress up or whatever. And so I was interested and intrigued. We went through the dynamics and thought that it really does help kind of people go through a visioning quest together, especially when you don't know people. And so we worked it out and we went through that.

So we designed a game called Imagine 2200. And that's actually where this game this comes from. We had the name for Imagine 2200 based on this game we played. And the whole game dynamic was to get them to dream about the future they want. What is 2200 look like for you if it's clean, green and just?

So we would start at the end of the game, actually. So we had everybody envision, what does a clean world look like? What does a green world look like? What does a just world look like? For the listeners, we transitioned to doing this all online. We used Miro, the infinite whiteboard thing that a lot of people use for this kind of exercise that you can do online. And we had a timeline. We had the end goal of 2200. We started at 2200 and we put people on a quest with five people that they didn't really know that well and were mixed group. And so everyone brought their talents and their self to the activity. So if you're with a climate scientist and you're with an activist, you're going to get a different thing than the person who's with a kelp farmer and a regenerative farmer and maybe like a journalist, you know? So we set people on these quests and they would populate it with different events, milestones, and things that they felt would be needed on the timeline to get us to 2200. We did this for three days, it's pretty wild, because it was supposed to be in person and we switched to online. And so I think we limited it down to two and a half days with lots of breaks.

Susan Kaye Quinn

Wow.

Tory Stephens

This was in the beginning of COVID and Zoom was this cool new technology. People were excited to do this. It wasn't a moment where people were like, God, I have to be online for two days. People were so excited and we designed it pretty well, it was well executed. And so we sent these people, each had a portal master or someone to help them, because there are some complexities to the game. And we realized, if they get stuck, we want someone there to help them move forward. So my job after the game was over was to then distill all the information that came out of the six timelines, because 30 people, five people in each, dreaming and putting stickies onto this timeline that plot between 2020 and 2200.

I came away after that exercise and did two things to pull down this information and make it make sense for me. I sat with them. I was given a lot of time, which I really am grateful for to Grist. So the event took place in April/March, and then I had the whole summer to figure it out, along with other duties that I was doing at Grist.

When I walked away, there was so many justice elements and so many things that many people—like old world, kind of green organizations—would have never thought of as living in the climate movement and what we need to get out of the climate crisis. So some of the things I'll name check that were new to me—I had heard about them but I didn't realize they were so important to people—were like the Land Back movement, the idea that indigenous folks should be given their land back, their ancestral lands, that they can be caretakers of that land a lot better than what we Westerners are going to be able to do. And the justice aspect, that that's the right thing to do because this was their land and as much as we can cede back to them as possible… I think is a really strong idea and a good one to kind of look to and have as a guide. I didn't realize how powerful that movement was and it came through on a couple of the boards. Like we definitely have to have it. People said it in a variety of ways, you know. Reparations for Black and brown people were on the list. You know, the idea that Black and brown folks, because folks that have ancestors that went through slavery, should be compensated for that trauma and that harm and that just egregious and horrific past. What else was on there? Abolition movement came through. So folks that believe that we don't need prisons and that we should have a restorative justice approach to prison and policing, that we could use almost zero police or none or less. There's kind of a spectrum of what different abolitionist folks believe. If you're a full abolitionist, then you want it all removed. But there was different feelings on the board with respect to people being there. But the idea that we can do better with folks that are incarcerated and having them return to regular society and also not having them end up in prison in the first place for like marijuana charges and things that folks on the board didn't see as the most important place that we're pushing for justice.

There's so much on these rich boards. So I used for each board, I used wordle, these word clouds, not wordle, wordle is a game on New York Times or something like that.

Susan Kaye Quinn

I knew what you meant: the word clouds.

Tory Stephens

Word clouds. So I took all the words, every single word that people had put on the board. To see which words were coming up big, things like intersectionality, community, culture, diversity. Some more bigger than others. The biggest word was community. Many of the boards had climate solutions, the word climate justice, that kind of thing.

So I was done with the information gathering piece. And I knew that what we wanted at Grist was climate fiction that was intersectional, that leaned heavily in the kind of cultural space as opposed to just being like sci-fi. I'm using a really broad brush, but some sci-fi is very heavy on the world building, but like Black culture won't be there. Everybody has the same blue kind of badged kind of outfit that's, you know, it's very sterile sometimes. One thing I do appreciate about Star Wars is the cultural aspects, the world building, they'll have like… you can tell that there's this kind of like anthropological… like the characters there have culture, what they're wearing and religious styles that they'll have and believe in. So I knew that we wanted something that really leans into the culture. We knew that we wanted a global kind of aspect to this. And I still can't remember why we decided to make it a contest, which is kind of interesting. I'm going to have to go back to the team and be like, where did we start to get on that train? But we knew that we wanted to engage the public. We wanted writers of all walks of life, in all levels, to contribute because we really wanted the exercise that we did with these people to come through in a way for other people. We thought it was such a moving experience, this idea to dream of the future. There's something about dreaming about the world you want that's really important. And that's what I walked away with.

When you think about it from like an abundant… like forget the world we live in right now, and the constraints we have now politically, culturally, societally… just the exercise of thinking about what you want helps you hone in on, Wait, what do I want for the future? What do I want for my kids? To be honest, at first it was like, it's a weird exercise. I was actually someone who wasn't into this whole thing, the visioning.

Susan Kaye Quinn

That's funny.

Tory Stephens

I thought visioning was a bunch of woohoo. My background is, I was a fundraiser for years before I joined Grist. I've done creative projects. I owned my own clothing company at one point that was a creative project and very much like an art kind of political stance project. And so I've done creative things before, but visioning I thought was just… the idea of looking to 2200, and so far in the future, I was like… I'm going to let this play out because I'm not going to get… like I trust my team, but I was definitely the one in the room, being like a little bit…

Susan Kaye Quinn

You were the skeptic.

Tory Stephens

I was definitely the skeptic. Yeah. And so now I, after the exercise, I saw all the beautiful visions that came out of that and how even knowing what you want for the future helps you work towards that now in the present. Like you can start laying the seeds for that now. You don't have to wait till 2200 to have reparations for Black folk. You don't have to wait to have Land Back for Indigenous folks to 2200. To be honest, some of the boards that people had, the timelines, some of them had big things like reparations for Black and brown folk at 2110, but it doesn't have to be 2110. You know, it could be earlier. It really is just this blue skying about it. There's something also fun and exciting about doing it collectively because you get to see, instead of just your own… I encourage people to kind of write down their vision for the future in their journal. I think it's a really great exercise, but if you can get people together in like a barn or field or around a fire and have a discussion, I just think it's a really good thing to do. I will say that if you're not trained to do this and you haven't done this, it might feel weird at first.

Susan Kaye Quinn

It's hard work.

Tory Stephens

It's also just like… we don't think about this. I'll say this too around the word hope, cause that's another big part of Imagine 2200. I think it's weird to collectively talk about hope with friends, family and people. I'm less weird about it now because I'm so invested in this project, Imagine 2200. But yeah, we gotta talk about these things. And I think the writing about it is helpful because it lets other people see the vision that you have for the future, critique it, discuss it, pull it out of your head and onto the table and into the community.

Just to finish up the story though, around what do we do next to get this off the ground? The next month after I had finished reading through all these timelines and digesting that information was… we were going to pitch three different ideas that Grist was going to launch. And the senior team was going to look at those. We didn't know actually if climate fiction was going to be the one that would win out. We just knew that we wanted to start something creative that helps people vision futures. And so climate fiction was definitely like in the running. But we also thought we might do a mural project around the United States in different cities that essentially do the visual work of Imagine 2200. But we wanted to do it in those workers of the world style, FDR programs, to envision green jobs and solar, new industries in the world. To help people vision: just do you see yourself in that vision? Maybe you do now that it's this giant mural with all these people working collectively towards this green, clean and beautiful kind of image. And then the third one was an anime. So basically, instead of investing in all these different stories, like one, a short, similar to maybe the Chobani one that you see floating around.

Susan Kaye Quinn

Right. A production.

Tory Stephens

And just to finish up the story… So then the last thing I did… I thought I should do a scan of the environment of short stories and climate fiction that was existing. Kim Stanley Robinson, Octavia Butler, short stories, adrienne maree brown… adrienne maree brown has a collection of stories that I thought was super useful, called Octavia’s Brood. It's a little bit Afrofuturist, a little bit environmental fiction-y, but it just felt like it was super helpful, especially since a lot of the things that were coming through during the visioning session were what some would see as squarely in the climate crisis, like reparations and Land Back, but others call it like adjacent to. I don't think they're adjacent. I think they're very intersectional. This is the way movements work, is that you need to care about, each and every individual's… the tapestry that it is.

Susan Kaye Quinn

I love that word, tapestry. That's so good.

Tory Stephens

You want to lift all. Even though, like I'm a straight dude, but I care strongly for my queer folks. And I'm not going to like ever, ever give one inch when it comes to the rights that they should have as a human being. And I think, we need… that solidarity that needs to happen between all of us in all sections of the movement is important. And that's why these other ideas like Land Back and reparations, if they're important to other folks in your constituency and movement, then you better be listening.

There's also like clear crossover between the prison industrial complex and how it harms the environment as well as people. So it's not just that this is an issue for folks that are incarcerated, it's an issue for everyone. And I think that's the same for all those other issues that I was referencing.

And so I just did a scan reading the stories, to see what was interesting and what was popping up. And I felt like after that, I had like a complete view. And I was not doing this alone. I had a team. Paul Sturtz, who ran the Truth in Fiction Festival in Missouri. It was like a very much a literary festival. He was brought to the table to help me work this out. And Galia Binder was another person who helped. And then the rest of the resources at Grist, I was having a lot of different conversations with a lot of the team who was on the Fix team. Grist used to have this team that was called Fix that was mainly focused with working with these Grist 50 folks. And that's the team that I came from. It doesn't exist anymore. We've all been rolled into Grist, and it's this one Grist thing, one big family. And so then we just hashed out what we thought. And the main things that we came away with, that we knew makes something an Imagine 2200 story, was that it has to be really culturally authentic. So if the story's from Malaysia, like if someone's from Malaysia, they're going to feel like that story, that it's true to the life that they live and that it's really culturally authentic, that it's hopeful, that it has climate solutions embedded in the story, that characters are intersectional and that there's a decent amount of community resilience built into that community. And I think four years later, I think we have a decent amount of those stories that hit all those kind of points that I just addressed.

We launched the contest. And then the first year… I always tell this story because it blows my mind. I have a marketing background to some degree, because in fundraising, as you know, you get the emails all the time. I was the fellow sending you those emails and crafting them and putting widgets so that you notice that there's a donate button. And I did this when we used to send 60,000 letters a year to people's homes. And so it was similar. Making the leap to email wasn't too hard because, I don't know, there are these extra widgets that help you like a blinking button or whatever. It's the same thing. You're just trying to tell a story and communicate to get people to kind of care about the issue so that they want to give as well and they're invested. And so yeah, we launched the project and my boss was like, if we get 200 stories in the first year, I'll be very like, it's a success. And then the first year we got a 1100 stories from 95 countries.

Susan Kaye Quinn

Amazing. I love that. And it's continued. Like you are continuing to get entries. I know, sometimes it's, you get that first flush and you think, okay, that was it. That was all the stories in the world that existed. And now there will be no more, but that hasn't been true. And it keeps going.

I love so much about all of that story. As you were talking, I was just thinking, wow, this is just pinging on everything that I love about this work and why I do this work. So first of all, community. I love that it came out of a community visioning process. It's like so integral, so integrated, process and outcome. The idea of it being creative work. So you have to do the creative visioning just to come up with the creative contest. Like, yes, that is so perfect. And it's engaging.

I just recently, full disclosure, went through one of Grist's visioning processes myself, because you guys had another workshop and I just sign up for everything that Grist does because I'm a huge fan and also I want to know what you're doing. But it was fascinating to go through that process because it is inherently creative and generative. And when you have to imagine your own future, like what do I actually want to have happen? You are immediately invested, you're immediately engaged, you have to be creative, it's hard work. A lot of people, at least in our group, and I think this is true for everyone who does it, who at first blush in that kind of process is like, I have no idea how to imagine 2200, what? So you start with something that's closer. That is what you can imagine. And then you either think no, that's impossible, so that must be somewhere out in the future, so we'll just toss it out there… or it's something that's so next five minutes that I'm not thinking hard enough, like where we actually could go. And I think that's great because that is exactly the right realization to come to. Reaching for the immediate easy thing… that's fine to get active and moving right now and doing stuff. And we absolutely should do that—it is way better than doing nothing. But we need to also stretch a little bit and imagine: Where do I really want this to go?

And the arts… I'm so, so glad for many, many reasons that you decided to pick Imagine 2200. Not that I don't love the mural idea, because I actually do love that idea, like a lot. I kind of want to see that happen as well. And I'm not into anime, but I know that there's a huge audience for that. So that would also have reached a lot of people. But with Imagine 2200… it's one of these ideas that is so generative because it gets people engaged in the process.

So first of all, it's arts. And arts are as Penn Garvin, who was on a previous pod, she's movement builder and she talks about how everybody has different talents and whatever it is that motivates you is the thing that you should do to build movement. Because there is a space for everybody's talents in movement building. And she said, but especially if you're in the arts, because the arts are what hook people in and engage people. It's storytelling, it's art, visual art, it's music. Music moves people at like this way deep level that we aren't always able to access. It says things we can't say with words. And so she's like, the arts are so powerful, don't think that you can't use that in movement building. We need you. We need that work. So first of all, it's arts. You're like front and center. We're making arts about this thing that we're doing. And by the way, we want you to do it. So you're asking people around the world to do that process, to do the visioning process, put it down in words.

And this is a thing that I've been thinking a lot about lately as I get super busy doing podcasts, which is great. Writing, also great. But other things… the thing that is most, I don't want to say most important, because there are many things that are important. One thing that's critically important when we're doing this kind of work is manifestation. You have to manifest it in the world in some way. So a story is a manifestation. You took the time, you put it down in words and that, that is forever, my friend. You just made it and unless your hard drive gets erased and it's permanently blocked from the world, you know, it will be around. A podcast even, like the conversation we're having, because we're having it not just between the two of us, but between us and the audience. And we take the time to manifest it into the world. There's a bunch of people who can, at their leisure, whenever they get around to it, it might be now, it might be a year from now, will go back and look at Episode 12 and go, you know what, there's that thing that was about Imagine 2200, let me go look at it. And so because you manifest stuff, it can go out and do things in the world for us.

And you won't know. It's that seed that you plant that you're not ever gonna know the outcome of, per se, although sometimes you do. I do have people come back to me all the time and say, this thing that you said or this thing that you posted or this thing that you wrote impacted me. It had an impact and now I'm gonna go forward and do my own writing, my own visioning, my own work to build these better worlds.

Tory Stephens

Right.

Susan Kaye Quinn

So Imagine 2200 is manifesting not just those 12 stories, all right? You have caused 1100 stories in 2021 to manifest into the world, is what you did. And those people and those stories touched people and did something. And so now as you build every year, you're growing, and it's not just that... it's like the metric is not how many stories you publish per se or even how many readers you reach. I think it's more like how many stories you cause to be manifested.

Tory Stephens

Mmm, that's interesting. Yeah.

Susan Kaye Quinn

I think that's the most powerful part of it. And at least that's the generative seed that grows into all the other things. You know, somebody cannot read the story if somebody didn't write it. So I love all of that. I love this entire story of how it came to be. I love that it was a game that you started with like a D&D-esque approach to this. And I'm not a gamer per se either, but the one kind of game that I do enjoy is cooperative tabletop games. I like those because they're cooperative. We're all on a team and we're all going towards the objective. And I like those because they require you to interact with your other players in a mode that you're not… like we actually do cooperate all the time in the world. And yet… and it's okay to have competitive games, it's fun, you know, but we need to exercise our cooperative muscles. And we need to say, hey, this is fun, not just I have to compromise and I don't like what you're doing, but we have to work together. Like, let's work for a higher cause together. Maybe it's just winning this game or maybe the game is solving climate. Daybreak is a game, tabletop game, which I highly recommend people do. But I love that you're accessed this visioning thing through a cooperative gaming exercise. I'm like, yeah, checks out. That is exactly how you would do that.

All right, moving on… I had another question I was gonna ask you about this weaving together of people and resources, which was your original position in Grist. And then that kind of evolved into Imagine 2200, which was like the ultimate of bringing everybody together to do something.

I feel like Imagine 2200 goes beyond just manifesting the stories and getting the word out, but you also connect the writers. And that was one thing that was really impactful for me as a writer.

I actually wanted to submit to the first round and didn't, because I was busy with my own projects. And so the next year I was like, I'm gonna submit. But then my life took this really hard left turn and I was like... I hadn't written for nine months. It was a terrible time for my personal life. And I literally had to go and lock myself away in the Chesapeake Bay in the tiny house to write. And this story was one that came out of that time. But again, that sense of isolation is kind of very representative of how I felt as a person writing these stories. I didn't know people who were writing these stories. And it wasn't because it was like for lack of looking. I just couldn't really connect with or find people who were… climate fiction, sure, but hopeful climate fiction? That was talking about social justice issues? I knew I couldn't be the only one on the planet doing this, but it sure felt like it. And so when Imagine 2200 came along and I was now part of that community of writers, that was hugely impactful to me. And you had a thing afterwards where our cohort, I was in the 2022 cohort, that you had a Zoom and we connected together. And so I was wondering if that… is that an organic thing that came out of just how the contest evolved? Or was that planned in from the beginning? Like, we also want to have these writers network together and work together and talk about how you create story like this.

Tory Stephens

Yeah, I would say that that was something we thought about midway through that year cycle. It's kind of interesting is that the Fix team, the team that I was talking about earlier that was embedded in Grist, that was… it wasn't a separate nonprofit. It was just a different team working on bringing folks together through retreats. And we also produced a magazine that was kind of a thematic magazine as opposed to kind of what Grist does, which is everyday news. So sometimes we have a food magazine or like, what would the future of sailing look like? Different kinds of thematic things. We on that team very much had in its ethos, this idea of bringing people together for cross pollination and networking. And so we already had done so many online gatherings to bring people together. Usually when we do a gathering, we always ask folks like, are you okay with sharing your contact information with the other people on this call so that if you would like to network with them. Our whole big thing was if we could get people that are in different industries to collaborate with each other… because we often saw the climate solutions, you're working on kelp farming and I'll use them again as an example. But like, is there a way to integrate other climate solutions like floating solar panels… just let's kind of think about the solution in a more dynamic way. And I think you can do that when you bring more people to the table. So we used to do that a lot with the gatherings we did. So I thought like, why don't we try this with the writers. These writers are from across the globe, they do not know each other. Maybe some of them do because they're like solarpunks or whatever. But, what I found at that time was that many folks didn't know each other just because they're just not a forum. There's many different forums, but not for the type of storytelling that we are trying to bring, which is that hopeful climate fiction and community resilience driven storytelling. And you saying that just now, like reminded me how… like I've seen you, you know, you've interviewed a few people that are a part of the imagine 2200 cohort that you are a part of, but then you've reached out to folks beyond that cohort. And I love that. It isn't something we've done—I think we only did it that one time and I would love to do it again.

I guess I'll pivot now to talking about this idea of this advocacy work that I've been doing as part of my role because I've noticed this thing. I've connected with a lot of different storytellers and storytelling outfits, and we all come back with the same finding, which is that there's not a lot of foundation funding for the work that we're doing. Imagine 2200 is resourced by Grist, but it's not resourced independently. So if Grist was for any instance in trouble in the news division, they would definitely cut my project because news is the core thing that happens at Grist. And I completely understand that. It's been a news organization for 25 years. That's the core product. Fortunately, we're in a good financial situation where we're really doing well. The balance sheet is strong and it's been strong for a while. We have a union now. There's a lot of great things happening at Grist that make it kind of strong for the next five to maybe even longer years.

Susan Kaye Quinn

That is super good to hear, because I need you to stick around, okay? This is very important to me.

Tory Stephens

It's one of those things that make me feel really comfortable, being able to do this work and not feeling stressed and, plus I work with a really great cohort of folks across the agency, both the news section and then just on our small team, Imagine 2200. But when I talk to other folks, it's still the same issue and they don't have a Grist to be the engine and the face that can kind of… you know, they don't have a development team of six people and things of that nature.

So what I want to say to the audience out there is like support your climate storytelling outfits because we need them and they're not well resourced. And some of them are like on the brink of, you know, they just don't have that foundation, not even foundation, but the major donor and regular average donor support, they could go away.

I'm going to make the case real quick for why I think that climate story, like why climate storytelling? Like there's so many other climate solutions that you could put your money into, but I think climate storytelling is the cheapest solution to imagine the future that we need and want. And these stories help motivate other people to act and dream and know that there's other people out there that care about the world in a way that they care about the world. And then there's the rich discussions that I think are necessary discussions that aren't… like the news gets us discussing things, but then three days later, there's a new thing, right? That we have to react to, comment on. And those things are important. I'm not discounting the news in any way. I think the news is like really important. I think facts are important. I think science is important, but I think storytelling is something that humans… it is just a part of our like DNA, right?

Susan Kaye Quinn

It's a huge part. It's a huge part of just how we interact with each other. So I feel like if we're not using fiction, if we're not using storytelling, even if you're using nonfiction storytelling, but you're not doing the imaginative fiction part, you're just leaving stuff on the table. You're leaving tools unused and they're among your most powerful tools and you're not using them. Like, why? Why aren't you doing that? And I mean, that sounds a little accusatory and of course I'm defending my vocation here, but I really do feel like sometimes we get trapped in the present. That's completely understandable because the present is very oppressively present. It demands a lot of us right now just to survive. And so I very much get that. I very much feel it.

And that's why we need to empower our storytellers because those are the people who… like, that's what they do, is lift up out of that present and help us see the future and imagine the future that we want, right?

I would love to hear from you and maybe you wanna do this after the pod and give me links, but I would like to know who these organizations are that are maybe on the brink and vulnerable and precarious that we can support.

Tory Stephens

Yeah, I'll definitely name a few. I don't know if I can like match up like which ones are on the brink and which ones aren't. I think that generally what I've seen from the folks that I'm in contact with around climate solutions is just that they're spending way too much of their time raising money.

Let me step back by saying what I noticed with a whole bunch of people is that the product—that's what we call things in the kind of media world, we create something, it's a product for people to consume. I don't really love the word but I'm gonna use it in this instance, just to show you the business side of things. The product (stories) is running ahead of the philanthropy that understands the need for this.

So what do I mean by that? There people are consuming Imagine 2200 stories. People are consuming climate fiction stories and are hungry for climate fiction stories, but philanthropy that puts the money behind this does not understand… like the production side is working. We're finding stories. We're finding really good stories, stories that are like A+, A-, A, B+… I mean, a B+ story is a really good story still. Like, I mean, I'll take a good C+ story with like a good plot.

Susan Kaye Quinn

Yes. Absolutely.

Tory Stephens

So those stories, the products are there. We have teams that are ready to do this. Like we have a full team at Imagine that, you know, cranks this out, understands how to edit a story, finds a good story, has a whole process. And then there's other outfits that are doing the same. When I say that there's other outfits doing the same, they're doing it, but with a slightly different take or style to storytelling that is quite different from Imagine, but is still necessary. And yet the philanthropic community, the major donor community, is just starting to catch up to the idea that this is a climate solution that you should be investing in because it changes narratives. It helps people think about this. It creates a space for discussion to happen that is necessary… it can happen organically. So some of the organizations, I'll just name a few.

There's Dear Tomorrow. Dear Tomorrow is an organization that, you can, write them a letter and you can write a letter to your future self, your future kid, your future community, a future president, like whoever you decide. The letter is really an exercise in you writing what kind of future you could write. But people do it from a variety of angles. It's not all about this future stuff. It could be like the grief you have about how I'm sorry we didn't act as much as we should but I'm going to try my best from this day forward. There's so many letters on there… and they're really, really, I mean, if you're someone who's a writer, I think it's a really cool place to immerse yourself… you can, you can gain a lot from reading these letters and the emotional impact that they deliver. Cause they're real people writing and they're public. So they, they house all the letters that people write. You know, some people do it like anonymously and other people are like, my name is Betsey Johnson and I'm writing to my son who's 12 or something like that. So Dear Tomorrow is one you should definitely check out. I think it's really fascinating what they do. They also do kind of museum art installations where the letters are on the wall and they have this globe with different words that are like swirling. They brought in an artist, a kind of installation person who is good at that and they show up at like Ted Connect, that's like their climate discussion and event that they have.

Another one is the Climate Imaginarium.

Susan Kaye Quinn

Yes! I know about the Imaginarium.

Tory Stephens

Those folks, they're amazing. Just for the listeners who don't know, it is a clique of people, an organization, but really a community of people that are working together to reimagine climate storytelling and be a house… it's not an influencer house like you see on TikTok, but it's like a creative house. It's a place. I say a house because recently the Climate Imaginarium was gifted a house by the folks on Governor's Island in New York City, in the bay there. It's like a 10 minute ferry ride to Governor's Island from New York City. So in one of the media hubs of the world, the City of New York. I'm one of the thought leaders behind the Climate Imaginarium. And so I just help them out. They do a lot more of the kind of organizing and on the ground work. But what we learned early on… Josh, who runs and is like the ED and the kind of main face of the Climate Imaginarium, found out that New York City invested $700 million or is going to, to create a climate solutions exchange and hub on Governor's Island. Governor's Island, which is this historic place that's been around for years, is going to be transformed into a climate solutions super space.

Susan Kaye Quinn

Nice.

Tory Stephens

And they're going to do that from a variety of angles, from the kind of climate solutions you think of when you think climate solutions. Many people think of tech solutions, even though that's not all of what climate solutions are. But New York also recognizes that arts, culture, and storytelling is like a huge part of their economy. And so they allocate… they want a part of this climate solutions hub to not just be like oyster revitalization and kelp farms off the ocean and solar farms and things like that. They also want it to be about the culture, the arts, and all that New York has to offer in those kinds of realms. So they gifted us a home, a house to the Climate Imaginarium. And those folks that are there are just running with this idea. And I'm on their WhatsApp, and it is so exciting to see these young people. I'll give an example of the excitement and the kind of DIY-ness of these folks. Somebody was bringing a whole bunch of plants or in things to… because they gave us this house, but we have to furnish it, everything, like all of it. And so plants and all the different things that would make it like a nice space were coming by just volunteers and different people that are tapped in. And somebody was like, I really could use, we could use a dolly. And someone was like, that's going to take a couple of days. And we already have people coming to the ferry today. And someone was like, you know what? I'm going to build a dolly and I'll have it there by 2 PM. And somebody like built a dolly like with wheels and it looks like cool and it's ready to go. And they're ready to do another one.

Susan Kaye Quinn

Amazing.

Tory Stephens

Somebody else built a whole bunch of stools that look really arty and neat and really nice woodworking. And so there's like a lot of energy. Again, the group has all this energy, but they could use a couple hundred bucks. Like it would go a long way with this young group of people who many just finished their Masters, at some of the colleges in New York.

So that's two. And then there is, I don't know if you know, if Arizona State University has an imagination…

Susan Kaye Quinn

Imagination and Climate or something is the name of their program, I think? (It’s Arizona State University, Center for Science and the Imagination.)

Tory Stephens

Yeah, they have a program and actually they have been super helpful for us. When we found out—I think this is the story now I'm finally remembering like where we came on like a contest and in submissions.

Susan Kaye Quinn

Okay. Yeah.

Tory Stephens

We were talking with Joey, who is one of the folks that leads the imagination space on Arizona State University. And they have an anthology that they publish every two years where they get submissions in. (This is ASU’s Climate Action Almanac that we highlighted the trailer of in Episode 9.) And we thought that was quite neat. And I read some of the stories. I thought they were cool. I got networked with some of the people in the anthologies that they've produced and also was speaking with Joey quite often there. We thought by putting some money up, it would like help motivate people. And we then went on like a learning tour of how do you do this and what's a reasonable amount of money and how do you deal with submissions? So we did figure that stuff out. But yes, I did remember through talking with Joey… like I'm not a writer and I don't submit to things. So I didn't even know about this, how the world of call for submissions work.

Susan Kaye Quinn

Right.

Tory Stephens

I really had to do a full education up and down the whole pipeline to figure out how do writers get their stories to market.

Susan Kaye Quinn

It makes so much sense now that you're connected with ASU, which is obviously part of the writing community, and Kim Stanley Robinson is tightly connected with them, and that they would be like, hey, have a contest. Yes, completely logical now.

Tory Stephens

They were saying you're going to have to have a call for submissions and maybe you want to put some money behind the prizes. That's where we started to think about that. ASU Joey was one of the first people outside of our networks that we were like, we want to talk with this person because of the cool people and the conversations they were having and the anthologies that they were bringing to light. Sometimes they have like—and we've been trying to do this or wanted to do this as pair (fiction and non-fiction)—and we did do this with this year's landing page. What we've found is that sometimes people submit stories that are amazing, but the climate solutions are kind of light. And we have so many climate solution stories we publish on Grist. So now on the landing page for Imagine, we showcase some of the other stories like yours, Seven Sisters. And we've seen a lot of like traffic actually because of it being reposted.

Susan Kaye Quinn

Yay! Thanks for doing that!

Tory Stephens

Yeah, no problem. And then we also have posted some articles that are like, hey, did you know that aboriginal folks have been burning land to clear the land and clear light debris so that controlled burns kind of help manage forests and whatnot. And then we have other stories that I can't remember right now, but on that page. And Joey was doing things like that before, where you have a fictional story, but then you bring in some scientists that know about the real world. And we thought that was really cool.

Susan Kaye Quinn

Yeah, I noticed that when I went to go look at the submissions page for this year's contest, because I'm always telling people about Imagine 2200, go write, you know, we need a million stories, get busy. And I loved that the way that, not just that you had my story on there, but that you had that construction of it, because the first question people have is, Well, I don't know how to do this. I've never done this before. Well, here's some examples. And here's some more information, you know, the nonfiction piece, again, tying that fiction and nonfiction piece together (see: Episode 9), because they are so integral. There's so many… I'm going to go back to that word tapestry that you had before, because I'm in love with that word, this is today's word that we're going to have to use a lot. But there is a tapestry in these stories, when you find one that really sings. It has all of that in there. It has the cultural piece. It has, like you say, the authentic place on earth. Where are you on earth? Who are the people who are there? And what is their experience of living there? And then what are the climate problems there? And what are the climate solutions there? And those are all real, but then you have to take this flight of fancy to get to the future and imagine. And so those stories that do that and have all that, there's a reason why they inspire me when I read them. It's like, yes, okay, this is what we're talking about. But it also is kind of a meta thing. And this gets back to one of the questions—I'm totally off script now because I'm like, this is a great conversation—but that woven tapestry… you can represent it in fiction because you have complete control over what you actually generate in your story. But in the real world, I feel like we don't connect as much as we need to, which is why I'm such a huge fan of the work that you're doing and have done to make those connections. So I love that you're part of the Climate Imaginarian folks and that you're connecting with ASU and have been all along and like that sort of weaving together, I think is critically important to grow this whole imaginative cloud of activity that we are manifesting, that we are generating.

To go back to your donor's issue… it reminds me a lot, I keep going back to Amitav Ghosh and The Great Derangement because his critique was so searing and so on point that it's a failure of imagination, that culturally as a society, we are failing to imagine the consequences that are already happening even. Like we're unprepared, but for what has already occurred. It's already happened and we still haven't like adjusted to that much less what's coming. And so we have, his critique was that in literature, we have a failure of imagination because literature's job is imagination. Its job is to imagine and interpret and understand culture and humanity. And for science fiction, the future, and increasingly for literary fiction also, is really climate fiction adjacent. So anyway, that was his critique. And I look at your donor situation and I'm like, okay. We're manifesting this. It's ground swelling. People want it. They need it. They're creating it. But the message hasn't gotten up. The failure of imagination is occurring at the donor level because they can't imagine that this is an important climate solution.

Tory Stephens

Yeah.

Susan Kaye Quinn

That is, I hope, going to change as we continue to manifest more and more of these stories. Everybody's working on their shoestring, but we're making it happen anyway. And thank God for Grist, cause you've got like actual staff that can do some of the heavier lifting work. There is a limit that you can do as an individual. We put that in our stories. Like we have to be in these cooperative community. We have to work together. And like, are we doing that in real life to make this happen? That's the key. That is the answer. And so, I love that you're doing it. I'm trying to do some of that. That's what a lot of the podcast is about to bring people, writers, people like yourself all into conversation, but also like including the readers in that conversation or the listeners and then directing them to: here's more stories and here's more organizations. So thank you for name checking those organizations. We will definitely put those in the notes.

Tory Stephens

Okay, great.

Susan Kaye Quinn

I'm also thinking about doing an episode where I look at some of the magazines that are specifically focused like Reckoning, Grist, of course, I don't consider you guys exactly a magazine, but same sort of space.

Tory Stephens

Orion, maybe.

Susan Kaye Quinn

Yes, and Little Blue Marble and a bunch of folks that have been doing work in this space that may not be widely known about. So try to lift some of that up.

Okay, so we're running out of time here and I have like totally taken up your time, but this is just such a great, great conversation. So what I'm going to do is tell people to go check out Imagine 2200. This episode should release before you guys close for submissions. Not too much before it, because I think it's the 24th of June.

Tory Stephens

There's 20 days left.

Susan Kaye Quinn

Yeah, so tick tock! So people probably won't have a lot of time to write a new story, but then you never know. But they might have one that they had already been working on that maybe they could rework and submit. So we'll get that out and highly encourage people to at least try. Or if you can't make it for this year's deadline, because I didn't make it for the first one either, come back next year. Imagine 2200 will be here next year. So start planning now or start practicing now. Start writing now and see what you come up with in the next year.

And then I try to end every podcast with a rapid round of three questions. So I'm gonna jump right to that.

So first, what hopeful climate fiction have you read recently that you would recommend? This is like the worst question for an editor and someone in your position, so I apologize. But I do want you to just like call out one that you really like or one that maybe spoke to you in a personal way. It's not like, you know, necessarily this is how you get an award winning Imagine 2200 story. This is just like Tory's favorite story. Or something like that. And if you want to take a pass, passes are also acceptable.

Tory Stephens

God, I'm trying to think of the name of the book. I just read it. It was so good. I'm reading a lot of short stories right now because of Imagine. And so I've been, even though we have reviewers, I've been kind of dipping into the stories to kind of just see what we're getting. So there have been a lot of good stories that I've already seen in there that I think are inspiring. And I could see being in the top 100, you know, a few, we still only, we have 200 stories at this point. And I think we're on track to probably get another thousand this year. I really live in the short story realm and I can't think of this novel that I just read. It was so good. (The book: The Great Transition by Nick Fuller Googins)

Susan Kaye Quinn

Well, you can send me the link afterwards, okay?

Tory Stephens

I will send you the link after. God, I can't believe my brain.

Susan Kaye Quinn

Okay, fair enough. I'm the worst with that too. Names of books or people, I just cannot.

Tory Stephens

Well, my daughter has been a little stuffy because of allergies. And so she woke up and was in our room last night and my brain, I'm just I'm going to blame it on baby brain, even though she's like she's the baby of the family, but she's eight at this point.

Susan Kaye Quinn

It doesn't matter how old they are when they come interrupt your sleep, right? You're just like, okay there goes my sleep.

Tory Stephens

Let's go to question two, but I'll get the listeners the story in my show notes.

Susan Kaye Quinn

Excellent. Okay, question two, what do you do to stay grounded and hopeful in our precarious and fast changing world?

Tory Stephens

Walks in the woods. There's this Japanese term. I'm going to use the English word for it. Forest bathing. And I will go in the woods. We hike a lot where we are. And I think it's really renewing staring out at water near trees, hearing the the birds and the rest of nature. I love nighttime nature, too.

Susan Kaye Quinn

Interesting.

Tory Stephens

The noises that you hear, like the peepers and the different things that you don't hear during the day, I think is really nice. And I know that not everyone feels comfortable going out in the dark in the woods, bring some people with you and but be quiet a little bit so you can hear things. It's just a whole other experience. So night walks are quite nice as well. You have to be careful because of the trails and whatnot. But there's just all these sort of sounds and you don't have to do anything like I'm not advocating for like, a complex hike, you know, something around water where there's nice paved, or even like dirt trails that's easy to walk. It's just nice to kind of do that at night. And my favorite is when it's like kind of moonlight where you can kind of see without a flashlight is really, I don't know, I just, I love spending time outdoors. And so that's one thing. And then my garden, we have native gardens here that we, I moved into a house in 2021 around the time that I started to Imagine. And the person, the couple who lived here before us was an ecologist who invested in native, like stripped all these like invasive and just things that are non-native. Of course we have some plants that are non-native, but we have like a meadow that has, you know, bee balm, lupine or lupin, depending on where you come from and how you call it. And just so many other things, golden rod and just really beautiful to kind of see that and how it feeds the animals and insects as opposed to things that are just there and kind of sterile for the environment. So that really gives life and gives me life and it's renewing. So, and then we also have a regular garden, like a food production garden, but that one is interesting and it's fun to do, but I really like the native stuff just seeing what pops up and what propagates in the battle that happens between these. So yeah, that gives me hope.

Susan Kaye Quinn

I love your night walk suggestion. I'm going to have to like try that because I actually do have a little forest preserve, a couple of them that are nearby and I have lived here for three years and I've never gone to them at night. So talk about failure of imagination, like come on, Sue. That's awesome. I love that. And yeah, the restorative nature thing is so real, like it's a real thing. I've got a book for you. I'm sure you don't need more reading, but the book that I'm reading right now, which I'm gonna also recommend for listeners is called The Light Eaters. And it's about plants and the secret life of plants, kind of, but it's really like plant intelligence and how they are animated and have electrical systems and respond to the environment and like there's a whole sort of evolving science field of botany that is kind of exploding right now and a little controversial about how much do plants actually feel and think. So it's very it's fascinating, I'm like way into it.

Tory Stephens

Hmm, interesting. That's really new too.

Susan Kaye Quinn

Yes, it is very new, it just came out and I'm reading it for research for my own writing, but I highly recommend for anyone who might be interested.

So, okay, and the last question, we kind of talked about this already about what's next for Imagine 2200. It sounds like we will have Imagine 2200 again next year, so people can count on that. Is there anything that maybe you haven't touched on that you would like people to know?

Tory Stephens

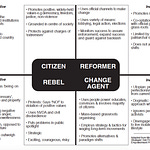

Yeah. So the experiment that we ran in that you took part in where the visioning piece. So we've been doing these visioning exercises with different groups. We made the conscious decision to try this out this year. We are asked to come to these venues at times like Ted Countdown and Aspen Ideas. And we often have a panel discussion with one of the investigative pieces that Grist has done. And we decided to do something different this year that was a little bit more, instead of being on the main stage, we were asked to kind of do a workshop this year. And I, and a few others were like, why don't we try doing a visioning workshop? We didn't do the one that you were a part of, which requires a whiteboard, like a online whiteboard. This was like with people, we ran two sessions at Aspen ideas. And we're just going to keep tinkering with that until we have a solid… I think you could probably tell that there was some kinks that we have to work out to kind of make this a better experience. But we polled everyone and I think like most people said that it was generative and great. We just want to make it so it's easier to be able to kind of get there. And the instructions piece doesn't take 30 minutes. Because that's quite an investment in people's time. So we're just trying to tinker with it, but yeah.

More stories from Imagine and then us helping lead collective visioning sessions for all sorts of teams. This doesn't have to be just for creatives. This can work for policy folks because we can kind of design it in a way that we can adjust it so that it works for folks in policy, campaigning, leadership development. There's a lot of ways that you can use this collective visioning experience and the idea of futurism to kind of get you out of your shell. And one of the things that we're exploring that somebody said to us at Aspen, they work at the Rocky Mountain Institute or how they call themselves now, which is RMI. They said that we have 10,000 people spread out across the globe and our culture issue of like keeping that together and sharing ideas. And we think that this visioning you're doing could be perfect to like get teams to kind of, across like, you know, someone in South Africa, they're sharing their vision with the person that lives in like Seattle and, you know, having a team come together and gel and, you know, be able to share ideas.

Susan Kaye Quinn

Yeah. That's fantastic to hear. I think you were the one who connected me earlier this year to a classroom where a teacher was doing a unit on climate fiction writing. And so I ended up like coming to that class, two different classrooms for like three different things. And we ran a whole unit on helping these kids to do that creative imaginative thing. And then we were doing it through a structured stories kind of process. And here you're talking about doing it more with a visioning process with adults. But that particular experience and, having done the visioning workshop, and listening to what you're talking about now, it's like taking it bigger. I'm really into that as a tool. I'm starting to see the potential of that as a tool to engage people in that imaginative process because if you have a failure of imagination, guess what? The answer is imagination.

Tory Stephens

It's a muscle!

Susan Kaye Quinn

Yes, it is. And you have to work on it.

Tory Stephens

The more you work on thinking about the future, your imagination, your crew, every… I believe that every person has a creative brain. Even the ones that say I'm an analytical person and I just don't think that they fed that side of their brain.

Susan Kaye Quinn

We are all capable of it and we need to use it. Like again, it's one of our tools that we are leaving on the table and not using and we need to get better at using it. So thank you for that work. Thank you for coming on the pod. This has just been a fantastic discussion and I so appreciate you and your time.

Tory Stephens

Thanks for having me.

LINKS Ep. 12: Building Movement Through Hopeful Climate Fiction with Editor Tory Stephens

Grist (Climate.Justice.Solutions), a nonprofit, independent media organization dedicated to telling stories of climate solutions and a just future.

The Grist 50: annual list of climate and justice leaders to watch

Daybreak, cooperative tabletop game about the climate

Dear Tomorrow, sharing personal climate messages

Climate Imaginarium, center for climate and culture

Arizona State University, Center for Science and the Imagination

ASU’s Climate Action Almanac—Bright Green Futures highlighted their trailer in Episode 9

The Light Eaters by Zoë Schlanger

The Great Transition by Nick Fuller Googins

An AI plots to take over a community’s solar power by Paolo Bacigalupi (Grist)

Under the Grid: Detroit goes full-on solar in this fictional future by Andrew Dana Hudson (Grist)

Ep 12: Building Movement Through Hopeful Climate Fiction with Editor Tory Stephens